January 17, 2014 marks the 20th anniversary of the M6.7 Northridge, California Earthquake, which caused the largest U.S. earthquake insurance loss to date. Similar to many of my RMS Californian colleagues, I recall clearly when the event occurred. I was working as a structural engineer in San Francisco, and we in the earthquake engineering community responded to the call to assess building and infrastructure damage.

When the dust finally settled 18 months later, the full picture of damage and loss emerged, and losses were dramatically higher than when first assessed. Direct economic loss reached $40 billion and insured loss totaled $12.5 billion, the majority from commercial and residential lines of business. It was an industry-changing event for the catastrophe modeling and insurance industry, as well as the broader earthquake engineering community.

Lessons Learned

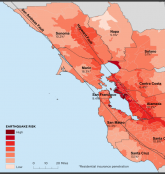

The Northridge Earthquake overturned a number of previous assumptions on earthquake science and engineering. The earthquake occurred on a previously unrecognized fault—a blind thrust fault—beneath the highly populated San Fernando Valley. This triggered urgent research to identify other blind thrust faults underlying the Los Angeles Basin and the San Fernando Valley, as well as other areas of California.

These hidden faults were incorporated into the 2002 version of the U.S. National Seismic Hazard Maps. The shaking also revealed new information around the vulnerability of certain classes of engineered buildings, in particular unanticipated welding failures at the beam-column connections of steel moment-resisting frame structures (SMRFs). This damage initiated the multi-year and multi-disciplinary SAC steel project, which investigated various repair techniques and new design approaches to minimize damage to SMRFs in future earthquakes.

The earthquake also overturned a number of assumptions on earthquake insurance risk management in California. Up until this point, the standard method of managing the risk was to employ a “probable maximum loss” approach that focused on the accumulation of insured exposure across the whole Los Angeles Basin.

Within the accumulation zone, the dominant risk was assumed to come from commercial structures. However, the majority of insured loss from the Northridge event actually came from residential properties—although residential damage was not extreme, the repairs proved very costly.

When the magnitude of the residential losses prompted insurers to restrict sales of homeowners coverage, the California legislature established the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), a publicly managed, privately financed entity, to provide coverage. In 1996, the CEA opened its doors for business and residential insurers could opt into the program. The majority of the California homeowners insurance market joined the CEA, and the aggregate share (of 70%) has changed little over time. However, the current take-up rate of residential earthquake coverage in California remains historically low—at approximately 10%. The CEA continues to explore ways to increase the take-up rates, as insurance is a crucial element in the recovery of an area and the reduction in federal aid assistance following a major California earthquake.

Risk Reduction Strategies

To commemorate the 20th anniversary, the earthquake engineering community is gathering in Southern California at the Northridge 20 Symposium. Local community leaders, emergency managers, financial insurance industry professionals, and scientists, and others are coming together not only to celebrate the achievements in risk reduction and management over the past 20 years, but also to determine how to become more resilient to earthquake damage moving forward.

There are various strategies around reducing the impacts of the next Southern California earthquake. These include the development and enforcement of seismic design provisions in building codes, widespread adoption of seismic strengthening techniques (e.g., to unreinforced masonry commercial buildings and older wood frame residential structures), and responsible land-use planning informed by accurate earthquake hazard information.

For example, the California Geological Survey (CGS) recently issued preliminary versions of new Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zone Maps for the Los Angeles region. Within Alquist-Priolo fault zones, construction of certain structures is prohibited to reduce damage and loss of life in a future earthquake. The new maps place the Hollywood Fault in an Alquist-Priolo zone, with major consequences for the potential redevelopment of Hollywood and in particular the value of some key land parcels.

Twenty years have elapsed since the Northridge Earthquake—and the industry has seen 20 years of relatively loss-free earthquake experience in California. In the most seismically active region of the U.S., a gap of 20 years—though a blink in geologic time—is an eternity for some consumers who increasingly question the cost of their earthquake insurance premiums. While the timing, location, and severity of the next major California earthquake are uncertain, the next major California earthquake is a certainty. We must remain vigilant in building a culture of prevention to reduce the impacts from this inevitable event.