The 2013–2014 winter windstorm season in Europe will be remembered for being particularly active, bringing persistent unsettled weather to the region, and with it some exceptional meteorological features. The insurance industry will have much to learn from this winter.

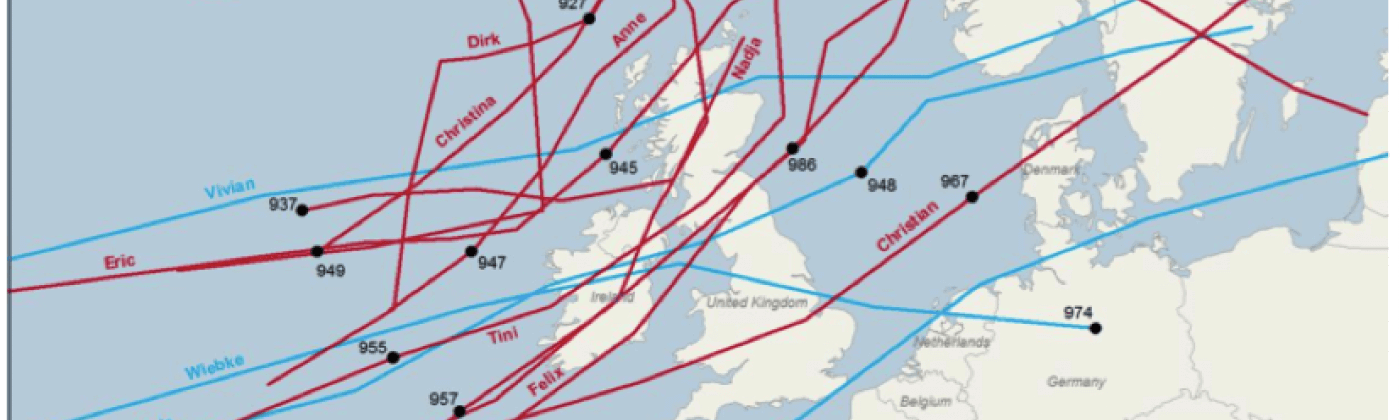

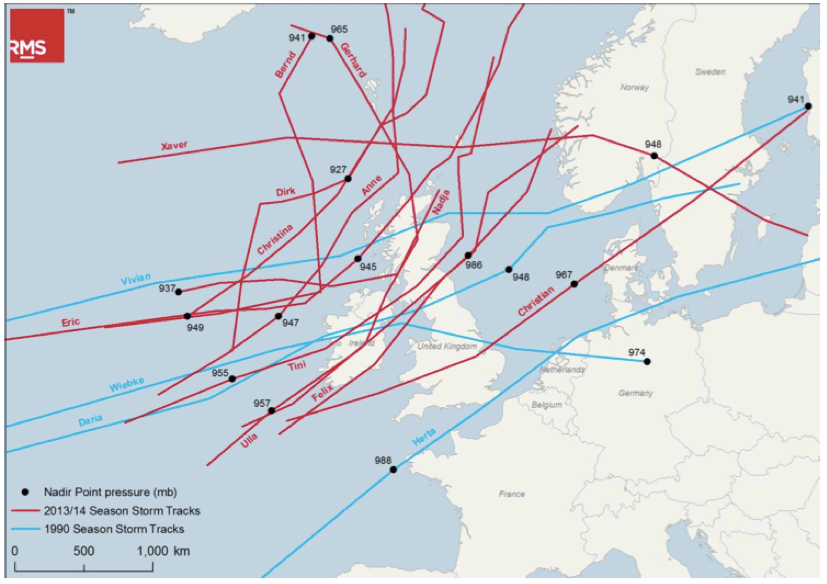

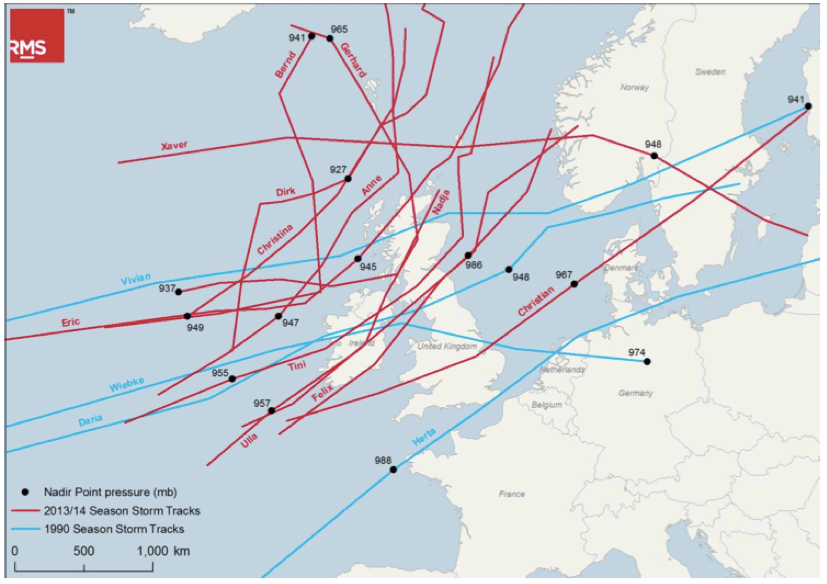

Past extreme windstorms, such as Daria, Herta, Vivian, and Wiebke in 1990, each caused significant losses in Europe. In contrast, the individual storms of 2013–2014 caused relatively low levels of loss. While not extreme on a single-event basis, the accumulated activity and loss across the season was notable, primarily due to the specific characteristics of the jet stream.

A stronger-than-usual jet stream off the U.S. Eastern Seaboard was caused by very cold polar air over Canada and warmer-than-normal sea-surface temperatures in the sub-tropical West Atlantic and Caribbean Sea. Subsequently, this jet stream significantly weakened over the East Atlantic.

Therefore, the majority of systems were mature and wet when they reached Europe. These storms, while associated with steep pressure gradients, brought only moderate peak gust wind speeds onshore, mainly to the U.K. and Ireland. In contrast, the storms that hit Europe in 1990 were mostly still in their development phase under a strong jet stream as they passed over the continent.

The 2013––2014 storms were also very wet, and many parts of the U.K. experienced record-breaking rainfall resulting in significant inland flooding. Again, individual storms were not uniquely severe, but the impact was cumulative, especially as the soil progressively saturated.

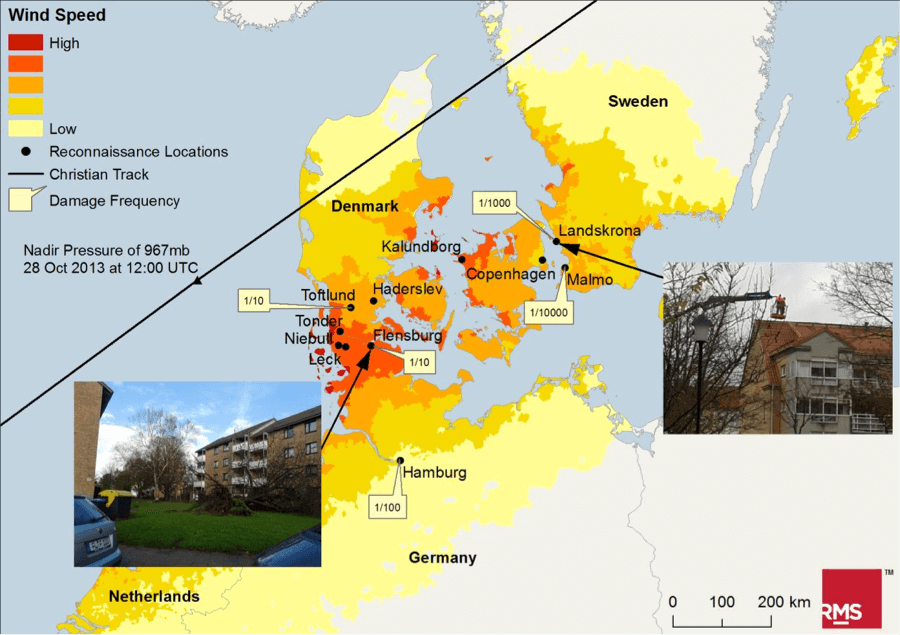

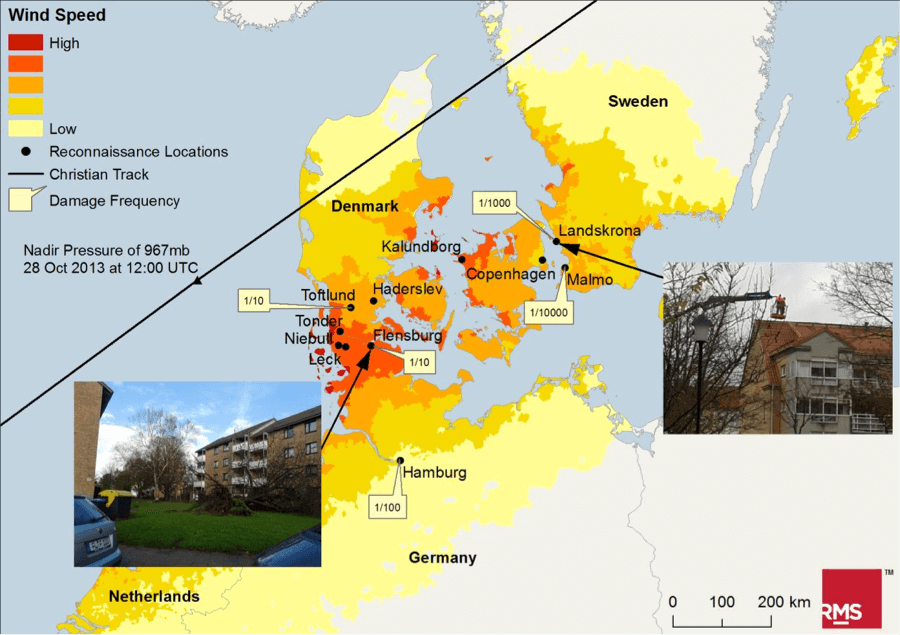

Not all events this winter season weakened before impact. Windstorms Christian and Xaver were exceptions, only becoming mature storms after crossing the British Isles into the North Sea and were more damaging.

Christian impacted Germany, Denmark, and Sweden with strong winds. RMS engineers visited the region and observed that the majority of building damage was dominated by the usual tile uplift along the edges of the buildings. Fallen trees were observed, but in most cases, there was sufficient clearance to prevent them from causing building damage.

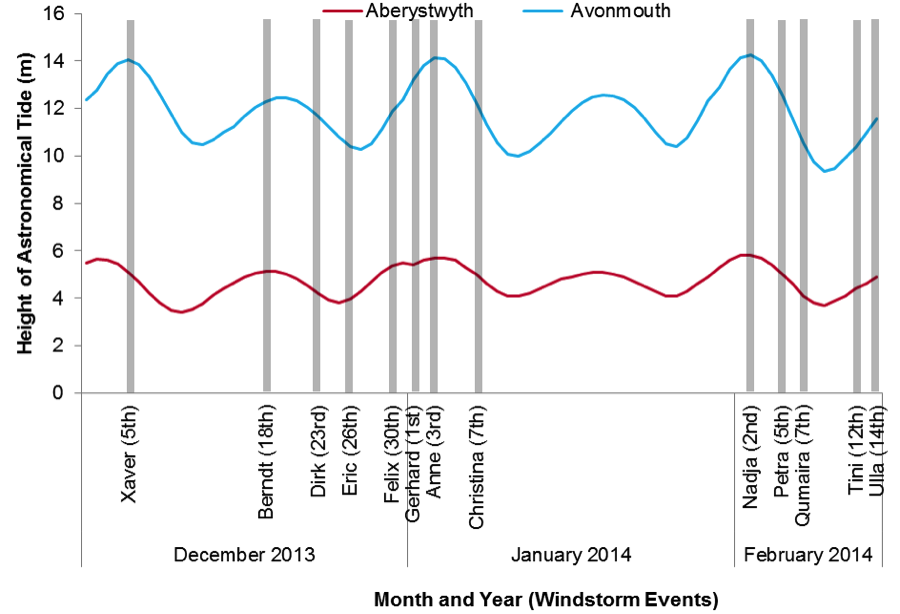

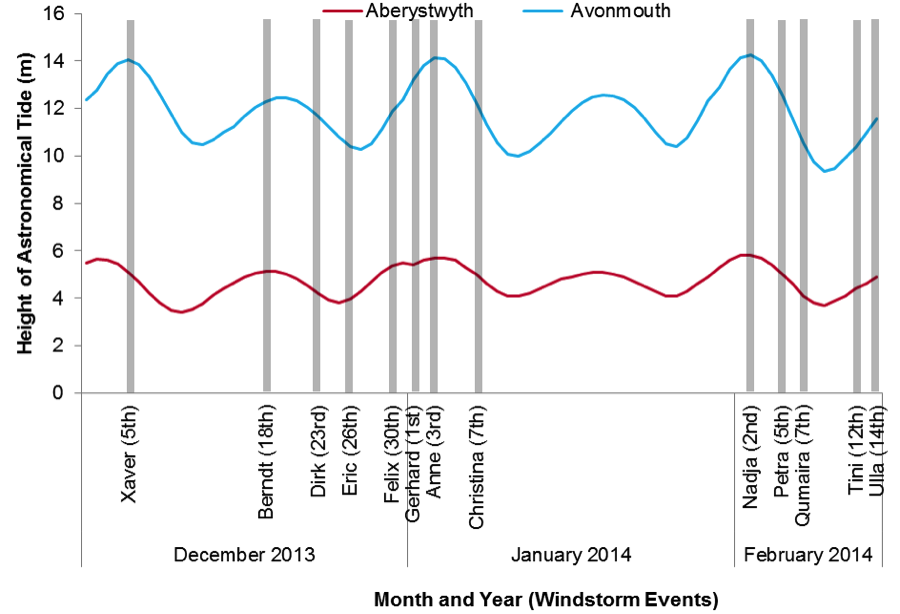

Xaver brought a significant storm surge to northern Europe, although coastal defenses mostly withstood the storm. Xaver, as well as some of this year’s other events, demonstrated the importance of understanding tides when assessing surge hazard as many events coincided with some of the highest tides of the year. The size of a storm-induced surge is much smaller than the local tidal range; consequently, if these events had occurred a few days earlier or later, the astronomical tide would have been reduced, significantly reducing the high water level.

Wind, flood, and coastal surge are three components of this variable peril that can make the difference between unsettled and extreme weather. This highlights the importance of modeling the complete life cycle of windstorms, the background climate, and antecedent conditions to fully understand the potential hazard.

This season has also raised questions about the variability of windstorm activity in Europe, how much we understand this variability, and what we can do to better understand it in the future. While this winter season was active, we have been in a lull of storm activity for about 20 years.

Given the uncertainty that surrounds our ability to predict the future of this damaging peril, perhaps for now we are best positioned to learn lessons from the past. This past winter provided a unique opportunity, compared to the more extreme events that have dominated the recent historical record.

RMS has prepared a detailed report on the 2013–2014 Europe windstorm season, which analyzes the events that occurred and their insurance and modeling considerations. To access the full report, visit RMS publications.