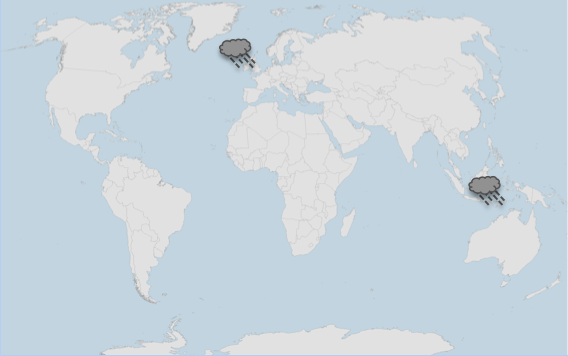

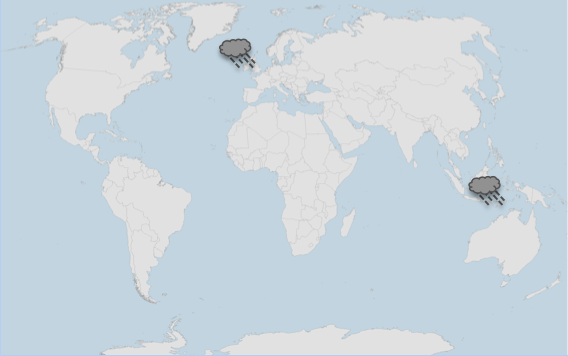

When it rains in Sulawesi it blows a gale in Surrey, some 12,000 miles away? While these occurrences may sound distinct and uncorrelated, the wet weather in Indonesia is likely to have played some role in the persistent stormy weather experienced across northern Europe last winter.

Weather events are clearly connected in different parts of the world. The events of last winter are discussed in RMS’ 2013-2014 Winter Storms in Europe report, which provides an in-depth analysis of the main 2013-2014 winter storm events and why it is difficult to predict European windstorm hazard due to many factors, including the influence of distant climate anomalies from across the globe.

Can we predict seasonal windstorm activity during the 2014-2015 Europe winter windstorm season?

As we enter the 2014-2015 Europe winter windstorm season, (re)insurers are wondering what to expect.

Many consider current weather forecasting tools beyond a week to be as useful as the unique “weather forecasting stone” that I came across on a recent vacation.

I am not so cynical; while weather forecasting models may have missed storms in the past and the outputs of long-range forecasts still contain uncertainty, they have progressed significantly in recent years.

In addition, our understanding of climatic drivers that strongly influence our weather, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO) is constantly improving. As we learn more about these phenomena, forecasts will improve, as will our ability to identify trends and likely outcomes.

What can we expect this season?

The Indian dipole is an oscillation in sea surface temperatures between the East and West Indian Ocean. It has trended positively since the beginning of the year to a neutral phase and is forecast to remain neutral into 2015. Indonesia is historically wet during a negative phase, so we are unlikely to observe the same pattern that was characteristic of winter 2013-2014.

Current forecasts indicate that we will observe a weak central El Niño this winter. Historically speaking this has led to colder winter temperatures over northern Europe, with a blocking system drawing cooler temperatures from the north and northeast.

The influence of ENSO on the jet stream is less well-defined but potentially indicates that storms will be steered along a more southerly track. Lastly, the QBO is currently in a strong easterly phase, which tends to weaken the polar vortex as well as westerlies over the Atlantic.

Big losses can occur during low-activity seasons

Climatic features like NAO, ENSO, and QBO are indicators of potential trends in activity. While they provide some insight, (re)insurers are unlikely to use them to inform their underwriting strategy.

And, knowing that a season may have low overall winter storm activity does not remove the risk of having a significant windstorm event. For example, Windstorm Klaus occurred during a period of low winter storm activity in 2009 and devastated large parts of southern Europe, causing $3.4 billion in insured losses.

Given this uncertainty around what could occur, catastrophe models remain the best tool available for the (re)insurance industry to evaluate risk and prepare for potential impacts. While they don’t aim to forecast exactly what will happen this winter, they help us understand potential worst-case scenarios, and inform appropriate strategies to manage the exposure.