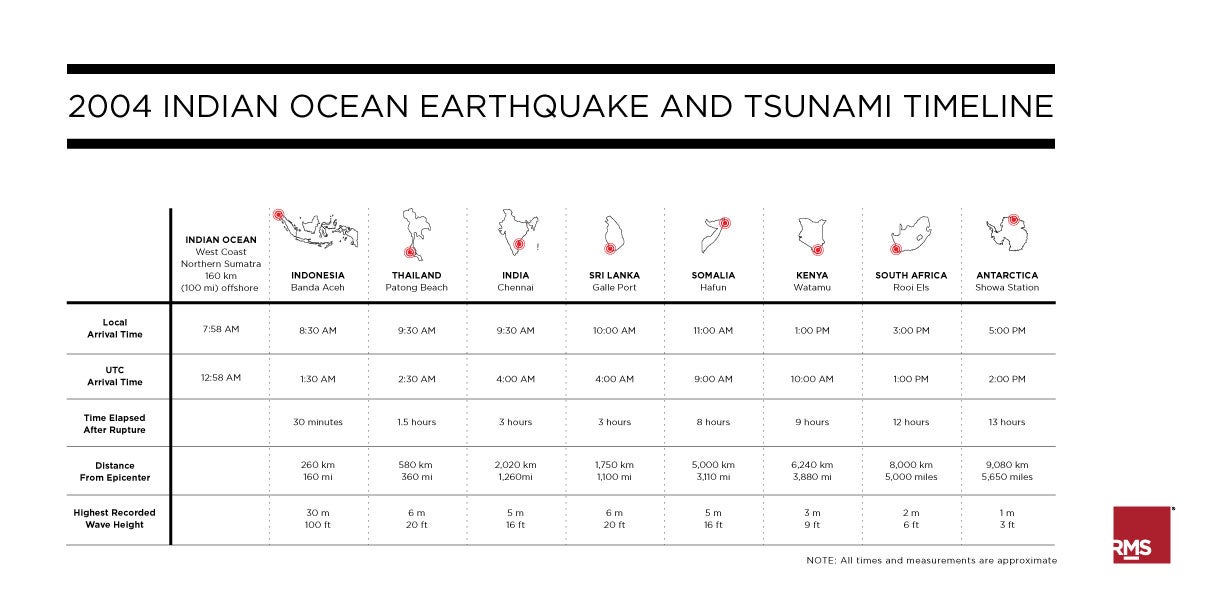

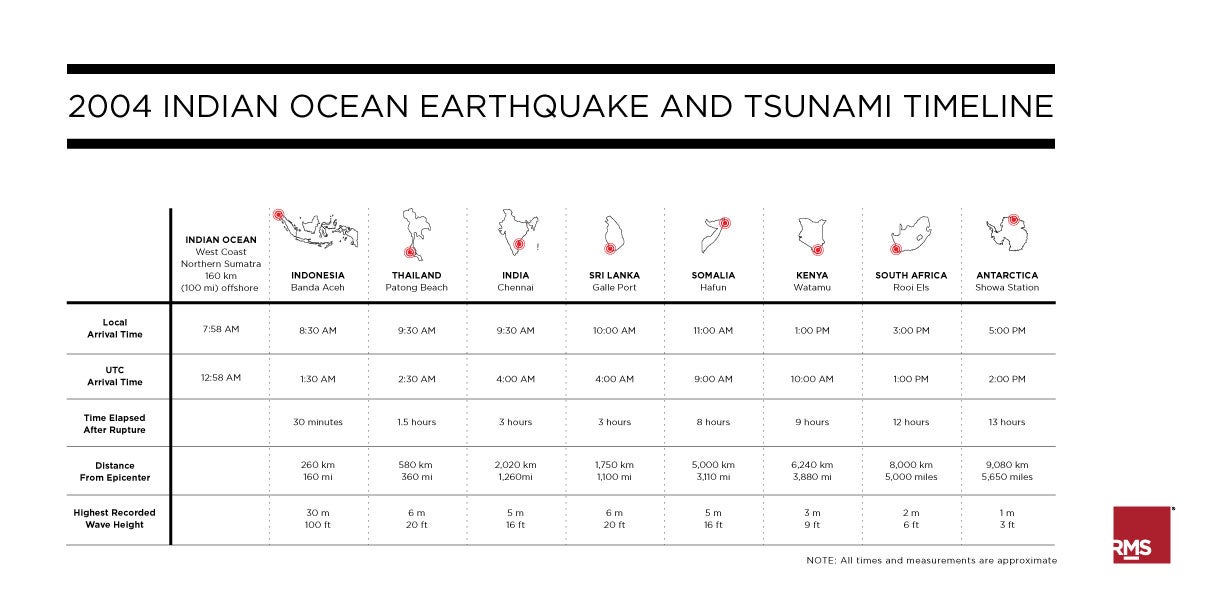

On Sunday, December 26, 2004 at approximately 8 a.m. local time, a massive earthquake occurred along the Indian–Burma plate boundary off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. Rupturing over 1,200 km of the Sunda Trench, the magnitude of the earthquake has been estimated between M9.0 and M9.3—with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Centennial Earthquake Catalog estimating M9.1. Occurring at a fairly shallow depth—less than 30 km—the earthquake generated a basin-wide tsunami that inundated coastlines across the Indian Ocean and caused run-up waves farther afield, impacting the eastern coastline of Africa. By the end of the day, it was apparent that the event was going to emerge as one of the worst natural disasters in modern times.

Click here for full size image

Economic Toll and Recovery

Overall economic losses from the 2004 disaster were approximately $10 billion, with the majority of loss attributed to the damage in the Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India. The large majority of property damage was caused by the tsunami waves. Along coastlines of most of the affected countries, buildings were situated closer to sea level than is typical of higher latitudes, exacerbating the impacts.

In the aftermath of the event, the international relief efforts across the Indian Ocean were seen as fairly effective. But the longer-term recovery work in certain regions has struggled—due to the overwhelming numbers of people displaced from their homes. There are, of course, examples of well-executed reconstruction efforts. Build Change—a partner organization of RMS—has worked with tsunami survivors in Banda Aceh, Sumatra to rebuild safe, sustainable homes. Ten years after the event, evidence of the destruction wrought by the tsunami remains in the high-impacted areas.

Humanitarian Impact

While tsunami in the Indian Ocean have certainly occurred many times before, from the perspective of modern history, the human casualties from the 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami have no historical equal. More than 225,000 people lost their lives in the disaster, with most of the loss of life occurring in the near field in Sumatra, Indonesia. In Indonesia, the tsunami destroyed virtually every village, town, road, and bridge along a 170-km stretch of coast less than 10 m above sea level. Sri Lanka’s Eastern and Southern provinces were severely impacted, with fatality rate among the population within 1 km of coast between 15% and 20%. In India, entire villages in Tamil Nadu were destroyed.

In Thailand, the tsunami affected local inhabitants and foreign tourists in the densely inhabited Phuket Island. The fatalities among the tourists were a significant proportion of the overall loss of life, as many were on the beach or in hotels near the sea at the time the tsunami waves struck. In addition, the initial tsunami wave in Phuket, which was east of the rupture, began with a receding wave. Many of the tourists (not indigenous to tsunami-prone coastal regions) were unfortunately not familiar with the nature of tsunami waves. In many (but not all) tsunami, the first movement of the sea is a withdrawal. Any occasion when the sea level recedes rapidly and inexplicably should be taken as a signal for immediate flight to higher ground.

Managing Tsunami Risk in the Aftermath

The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami highlighted inherent vulnerabilities in the world’s coastlines and the people who live there. Coastal populations are on the increase in many parts of the world, mostly due to the exploitation of sea resources or tourism-related activities. Adequate tsunami mitigation measures— such as tsunami warning systems, education, and land use planning—can be put in place to save lives, property, and the livelihoods of those living on the coast.

Although the impact of the 2004 disaster on the global insurance industry was minimal, it alerted the world to the dangers of tsunami hazards. Worldwide response to the 2004 disaster resulted in the establishment of the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System in 2006.

Ten years hence, the world has seen two more earthquake-induced tsunami events—in the 2010 M8.8 Maule, Chile Earthquake and in the 2011 M9.0 Tohoku, Japan Earthquake—causing many clients to inquire where else in the world can events like these happen?