Those were the words of the then Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, in the aftermath of two earthquakes on the same day, October 26, 2016. As a statement of indomitable defiance at a scene of devastation it suited the political and public mood well. But the simple fact is there is work to do, because Italy is not as strong as it could be in its resilience to earthquakes.

There’s a long history of powerful seismic activity in the central Apennines: only recently we’ve seen L’Aquila (2009, Mw6.3), Amatrice (August 2016, Mw6.0), two earthquakes in the area near Visso (October 2016, Mw 5.4 and 5.9) and Norcia (October 2016, Mw6.5). These have resulted in hundreds of fatalities, mainly attributed to widespread collapse of old buildings, emphasizing that earthquakes don’t kill people – buildings do. Whilst Italy’s Civil Protection Department provides emergency management and support after earthquakes, there is too little insurance help for the financial resiliency of the communities most affected by all these events. While the oft-repeated call for earthquake insurance to be compulsory continues to be politically unobtainable, one way it could be spread more widely is through effective modeling. And RMS expertise can help with this, allowing the market to better understand the risk and so build resilience.

Examining High Building Fragility

The two most significant factors for earthquake risk in Italy are (i) construction materials and (ii) the age of the buildings. The majority of the damaged and destroyed buildings were made from unreinforced masonry, and built prior to the introduction of the most recent seismic design and building codes, making them particularly susceptible. With the RMS® Europe Earthquake model capturing both the variations in construction types and age, as well as other vulnerability factors, (re)insurers can accurately reflect the response of different structures to earthquakes. This allows the models to be used to evaluate the cost benefits of retrofitting buildings. RMS has worked with the Italian National Institute for Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) to see how such analyses could be used to optimize the allocation of public funds for strengthening older buildings, thereby reducing future damage and costs.

Seismic Risk Assessment

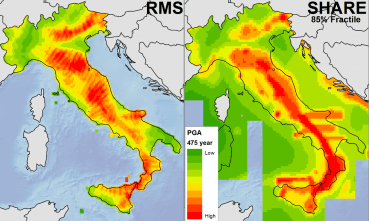

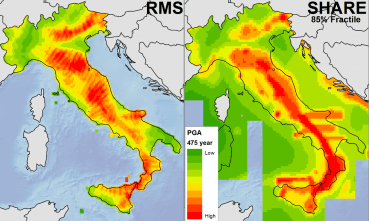

The high-risk zone of the central Apennines is described well by probabilistic seismic hazard assessment (PSHA) maps, which show the highest risks in that region resulting from the movement of tectonic blocks that produce the extensional, ‘normal’ faulting observed. The maps also show earthquake risk throughout the rest of Italy. RMS worked with researchers from INGV to develop our view of risk in 2007, based on the latest available databases at that time, including active faults and earthquake catalogs. The resulting hazard model produces a countrywide view of seismic hazard that has not been outdated by newer studies, such as the 2009 INGV Seismic Hazard Map and the 2013 European Seismic Hazard Map published by the SHARE consortium, as shown below:

The Route to Increased Resiliency

Increasing earthquake resiliency in Italy should also involve further development of the private insurance market. The seismic risk in Italy is relatively high for western Europe, whilst the insurance penetration is low, even outside the central Apennines. For example, in 2012, there were two large earthquakes in the Emilia-Romagna region of the Po valley, where there are higher concentrations of industrial and commercial risks. Although the type of faults and risks vary by region, such as the potential impact of liquefaction, the RMS model captures such variations in risk and can be used for the development of risk-based pricing and products for the expansion of the insurance market throughout the country.

Whilst Italy’s seismic events in October caused casualties on a lesser scale than might have been, the extent of the damage highlights once again the prevalence of earthquake risk. It is only a matter of time before the next disaster strikes, either in the Central Apennines or elsewhere. When that happens, the same questions will be asked about how Italy could be made more resilient. But if, by then, the country’s building stock is being made less susceptible and the private insurance market is growing markedly, then Italy will be able to say, with justification, it is becoming stronger than any earthquake.