The 2016-17 Australian region cyclone season will be remembered primarily as an exceptionally slow starter that eventually went on to produce a slightly below-average season in terms of activity.

With the official season running from November 1 to April 30 each year, an average of ten cyclones typically develop over Australian waters with around six making landfall, and on average, the first cyclone landfall is by December 25. For the 2016-17 season, we saw nine tropical cyclones, of which three further intensified into severe tropical cyclones and three of which made landfall, running contrary to an average to above-average forecast from the Bureau of Meteorology.

The bureau’s preseason outlook, released in October 2016, was primarily based upon the status of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Neutral to weak La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean and associated warm ocean temperatures in Northern Australia were expected to persist through the season. During La Niña phases, there are typically more tropical cyclones in the Australian region, with twice as many making landfall than during El Niño years on average.

Additionally, such La Niña conditions typically lead to the first crossing of a tropical cyclone coming more than two weeks earlier in the year than the climatological average. These conditions meant that probabilities were in favor of increased tropical cyclone activity in the basin, with the first tropical cyclone expected to make landfall in Australia during December.

The Latest First Cyclone Landfall in Australia on Record

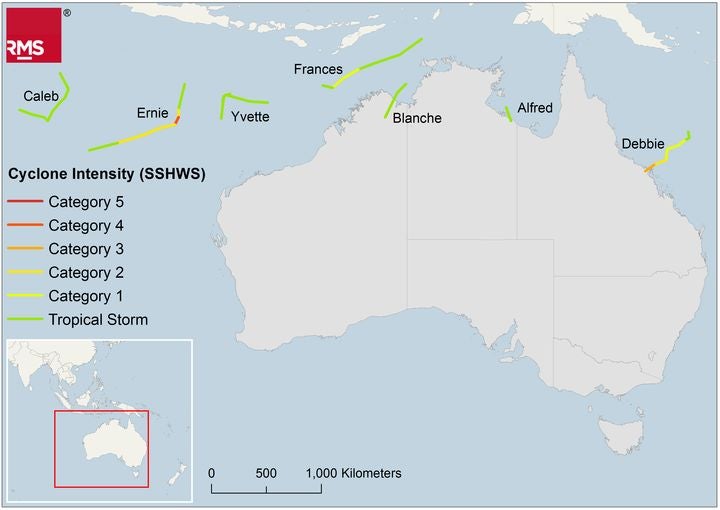

For the 2016-17 season, this was not the case as during the first four months of the season (November-February), a mere two tropical lows developed into cyclones (Yvette and Alfred). Cyclone Blanche set the record for the latest first cyclone landfall in Australia, which on March 6 crossed the northern coast of Western Australia as a Category 2 storm on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale.

What caused this slow start? The oceanic conditions were largely favorable, but the right atmospheric conditions rarely came together for cyclone formation. Warmer than average sea surface temperatures contributed to an early onset and highly active Australian monsoon season. The monsoon trough, a broad region of low pressure associated with tropical convergence and convection, was located much further south than usual, positioning the large scale rising motion needed for tropical cyclone formation on or near land, inhibiting the potential for cyclogenesis.

Where tropical lows did form over open water, they often struggled to intensify due to persistent moderate to high wind shear, only developing when the system drifted into lower shear environments over land. This resulted in so called “landphoons”, supercell thunderstorms whose radar signature resembles that of a tropical cyclone, which brought light winds but heavy rains. These systems resulted in an extremely wet Australian monsoon season with total rainfall in the Northern Territory 48 percent above average, the eighth highest on record.

This pattern of low cyclone activity early in the season was not only seen in the Australian region but across the whole Southern Hemisphere, with sinking air in the cyclone-forming regions of the south Indian Ocean and the southwestern Pacific. The hemisphere saw over 280 days without a hurricane-strength tropical cyclone, the longest period on record. For February 26, 2017, normally near the peak of the Southern Hemisphere cyclone season, total accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) was just 14 percent of the climatological average over the same period.

An Active End to the Season

Then, in contrast to an absence of severe tropical cyclones for the first four months of the Australia cyclone season, the region experienced three within March and April; enter Debbie, Ernie, and Frances.

Season summary map showing the tracks and intensity (Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, SSHWS) of all named tropical storms which reached at least tropical storm classification according to the JTWC during the 2016-17 Australian region cyclone season

Of these three, Severe Tropical Cyclone Debbie was the most damaging, making landfall on March 28 near Airlie Beach, Queensland as a Category 4 storm on the Australian scale, with PERILS estimating that insured property market loss will reach AUD$1.1 billion (US$802 million) from this event.

Following Debbie in early April was Severe Tropical Cyclone Ernie. Although Ernie did not impact on land, it was the first Category 5 cyclone (Australian scale) in the Australian region since Cyclone Marcia in February 2015 and was notable for its explosive intensification, escalating from a tropical low to a Category 5 severe tropical cyclone in just 24-30 hours.

Such cyclones act as a reminder that a quiet start to the season is not necessarily indicative of what is to come, with intense cyclones possible until the end of the season and even beyond. On May 7, Cyclone Donna in the South Pacific became the strongest Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone in the month of May on record, when it rapidly intensified into a Category 4 storm (Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale) as it bypassed north and west of Vanuatu. Donna damaged more than 200 buildings on the islands, proving damaging cyclones are possible even after a cyclone season has officially finished.

Ultimately, Severe Tropical Cyclone Debbie will be the storm remembered from the 2016-17 Australian Cyclone Season and a follow up blog examining this event will be published in early June.

RMS is targeting an update to the Australia Cyclone model for release in 2018 that will utilize the latest information from recent cyclone seasons, incorporating new Bureau of Meteorology data inclusive of the 2016-17 season and add several recent historical storms, including Cyclone Debbie, to the event set.

Potential Implications for the Atlantic

Despite the active end to the season, ACE in the Southern Hemisphere remains over 50 percent below average at 96 (104 kt2). Interestingly, in years where Southern Hemisphere ACE is below 200, the Atlantic typically also has a quiet season, averaging an ACE of just 77 compared to the 1981-2010 average of 104, although there have been notable exceptions such as in 1995.

The RMS 2017 North Atlantic Hurricane season outlook will provide more details on what is likely to be expected from the upcoming Atlantic hurricane season and is due to be published in June with an accompanying blog post.