Mark Powell, vice-president – model development, RMS-HWind

Michael Kozar, senior modeler, RMS-HWind

In a Safety Recommendation Report issued by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) last month, the Board took the unprecedented step of requesting that a fellow federal agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), together with the U.S. Coast Guard, act immediately to do more in improving maritime safety. The NTSB Safety Recommendation Report was released as part of its ongoing investigation into the tragic sinking of the merchant vessel El Faro, a U.S. flagged, 790-foot (240 meter) roll-on/roll-off container ship with a cargo of containers and vehicles, which sank with all hands during Hurricane Joaquin in October 2015.

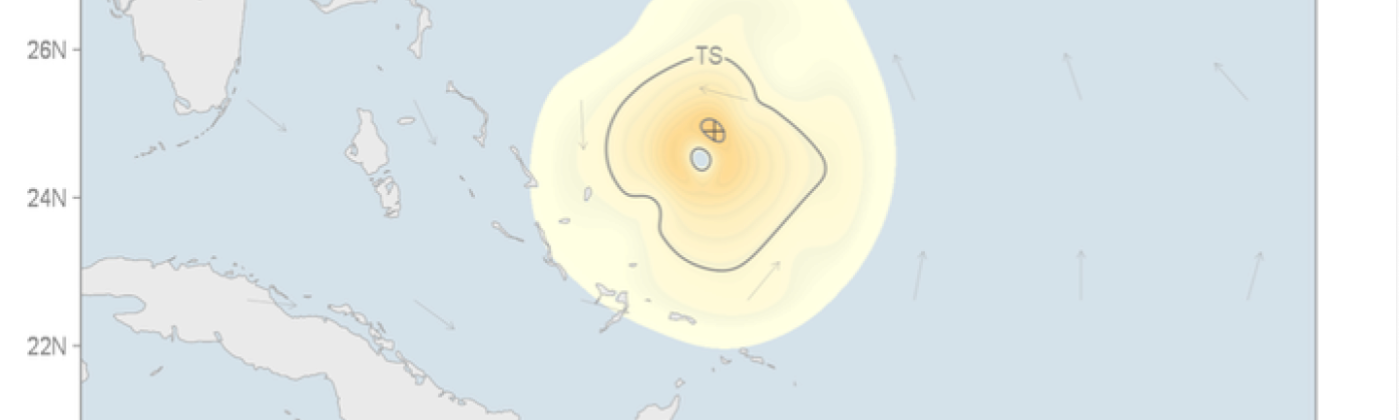

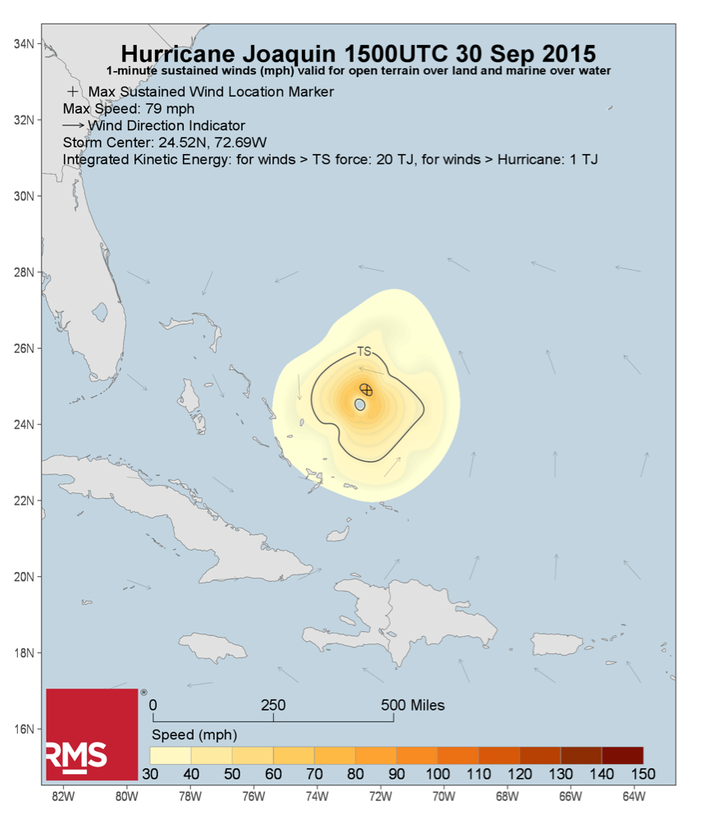

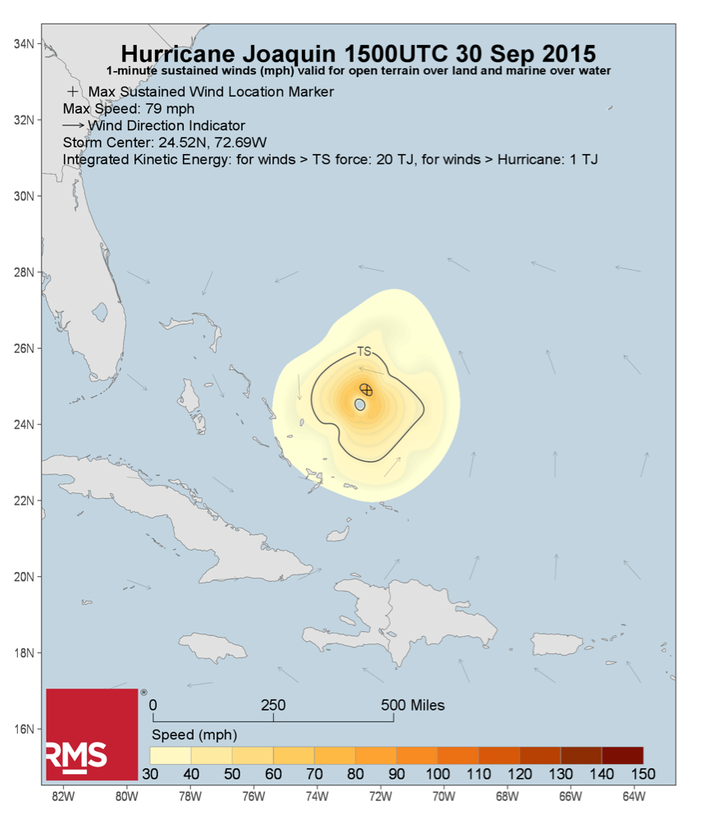

HWind snapshot for Hurricane Joaquin on 30 Sep, 2015, the day before the MV El Faro sunk near Crooked Island in the Bahamas. Joaquin intensified to about 125 mph on Oct 1, 2015 when the El Faro was lost.

The El Faro departed from Jacksonville, Florida on its final voyage shortly before 23:00 Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) on September 29, 2015, en route to San Juan, Puerto Rico. On October 1, 2015, at about 07:15 EDT. the U.S. Coast Guard received distress alerts, with the El Faro some 40 nautical miles northeast of Acklins and Crooked Island, Bahamas, and close to the eye of Hurricane Joaquin.

According to the report, just minutes before the distress alerts were received, the ship’s captain had called the ship owner’s designated person ashore and reported that a scuttle had popped open on its second deck and water was flowing freely free into the no. 3 hold. He said the crew had controlled the ingress of water but that the ship was listing 15 degrees and had lost propulsion. Both the Coast Guard and owners of the ship were unable to reestablish further communication with the El Faro.

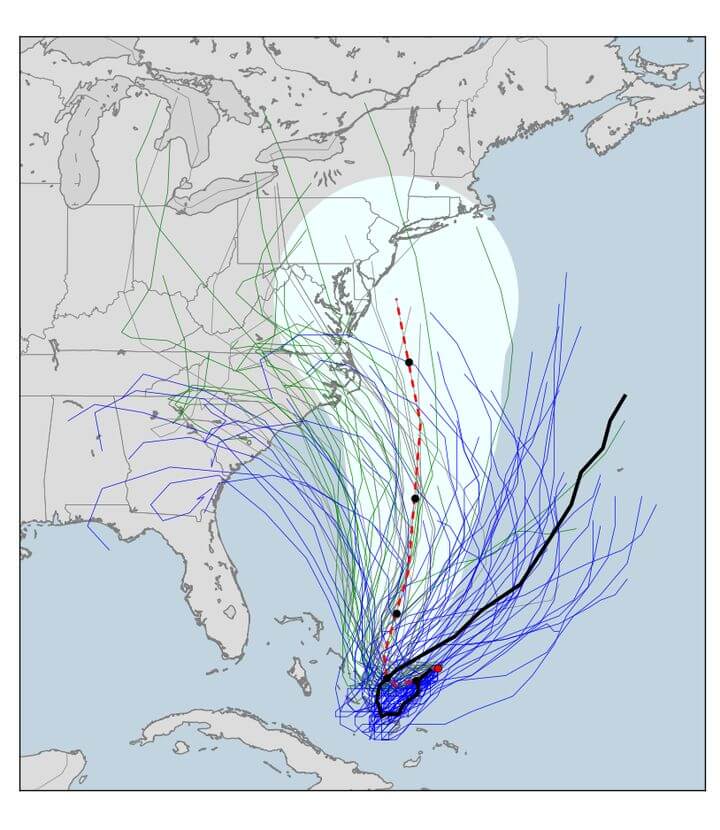

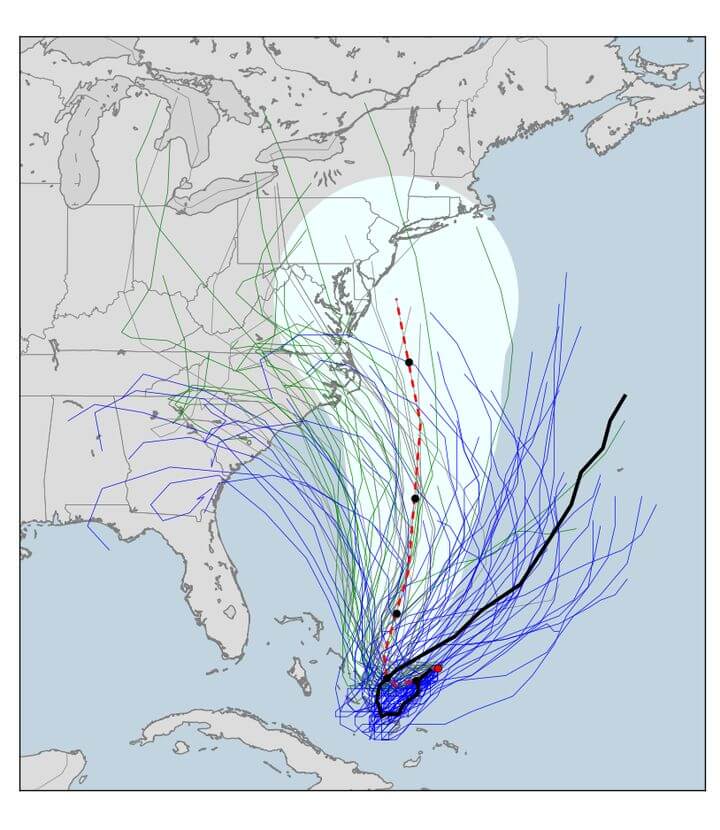

Forecasts for Hurricane Joaquin issued 15:00 UTC, 30 September, 2015. Actual storm track is in black, NHC forecast in red, NHC uncertainty cone in white, NOAA GFS model ensemble forecasts in green, and ECMWF ensemble forecasts in blue. Joaquin had a tendency to continue moving south early in the forecast period, in contrast to the forecast to the west.

Rescue attempts were severely hampered by the hurricane-force conditions at the scene. On October 5, after a debris field and oil slick were discovered, the Coast Guard determined that El Faro was lost and declared the accident a major marine casualty. At sundown on Wednesday, October 7, the Coast Guard suspended the search for survivors. All 33 crew members were lost.

The El Faro’s data recorder was found several months later and provided more details on the decision process associated with the ship moving towards the intensifying storm rather than avoiding it. The U.S. Coast Guard’s Marine Board of Inquiry heard testimony from National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecasters about the difficulty of forecasting Joaquin’s track as well as its sudden intensification in an environment with moderate wind shear.

The NTSB’s 21- page report provides “recommendations aimed at getting better weather information to mariners”. The NTSB was motivated to produce the report after noting that “several other major storms had significantly deviated from their forecasts” and that a “new emphasis on improving tropical cyclone forecasting was warranted.”

Improved understanding of hurricane forecast uncertainty is a big focus for the RMS-HWind group, and for attendees at the annual RMS Exceedance conference held in New Orleans this March, they joined discussions as we explored this effort in detail and highlighted many of the same cases mentioned in the NTSB report. Based at our offices in Tallahassee, Florida, RMS has been conducting research and development on this topic and have shared some of the ideas that we have been investigating, including our methods for distilling the huge amount of available forecast data into products that can help our clients understand the most likely forecast scenarios.

What was particularly gratifying to see was confirmation of our approach in the NTSB findings and recommendations, including a NTSB recommendation to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA):

“To the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Develop and implement technology that would allow NWS forecasters to quickly sort through large numbers of tropical cyclone forecast model ensembles, identify clusters of solutions among ensemble members, and allow correlation of those clusters against a set of standard parameters.”

Progress at RMS continues to be made towards developing unique hurricane forecast solutions for our clients, and we look forward to delivering new products in the near future.