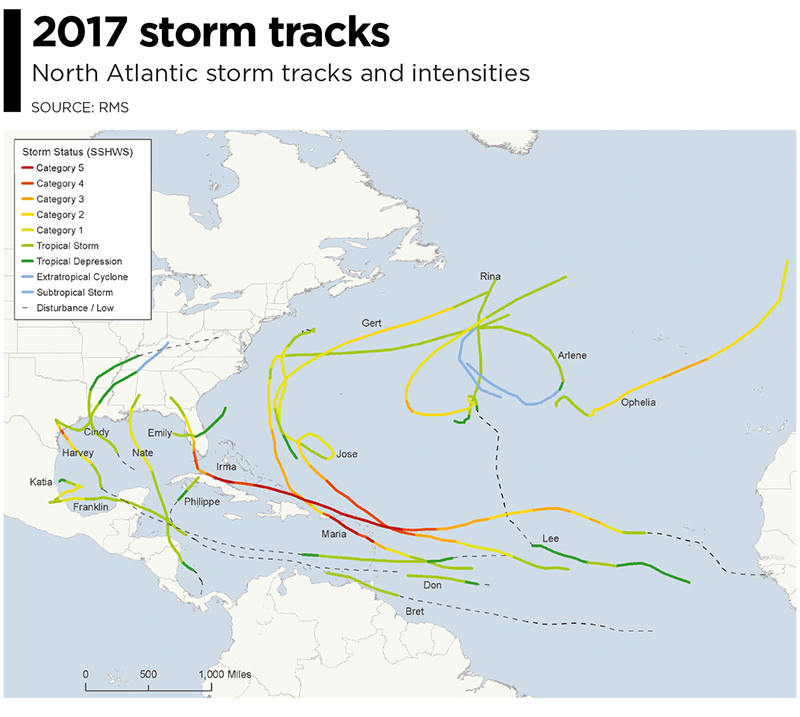

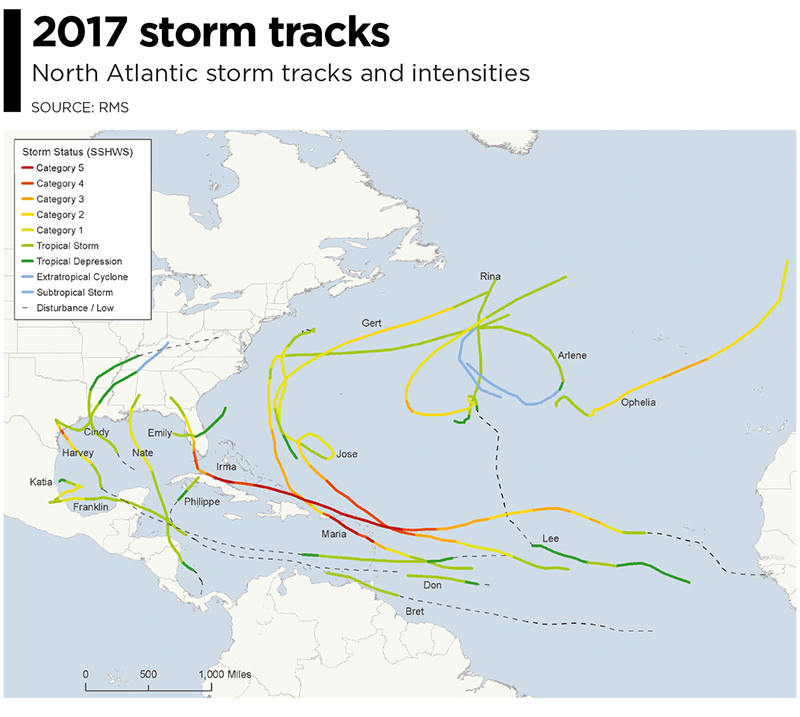

Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria (HIM) tore through the Caribbean and U.S. in 2017, resulting in insured losses over US$80 billion. Twelve years after Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma (KRW), EXPOSURE asks if the (re)insurance industry was better prepared for its next ‘terrible trio’ and what lessons can be learned

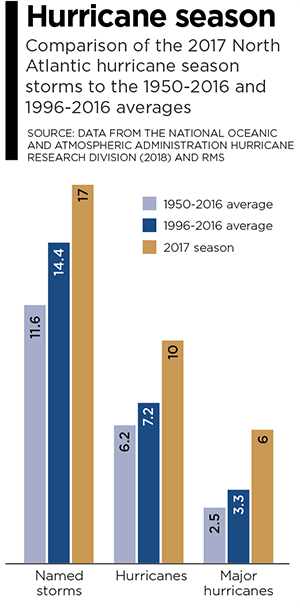

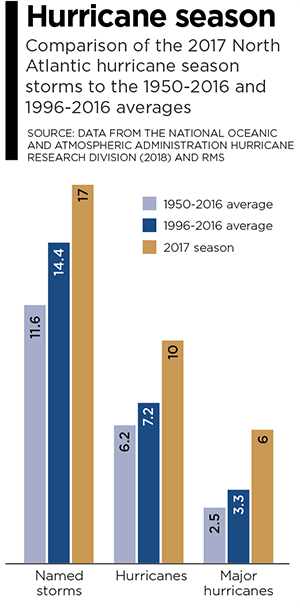

In one sense, 2017 was a typical loss year for the insurance industry in that the majority of losses stemmed from the “peak zone” of U.S. hurricanes. However, not since the 2004-05 season had the U.S. witnessed so many landfalling hurricanes. It was the second most costly hurricane season on record for the (re)insurance industry, when losses in 2005 are adjusted for inflation.

According to Aon Benfield, HIM caused total losses over US$220 billion and insured losses over US$80 billion — huge sums in the context of global catastrophe losses for the year of US$344 billion and insured losses of US$134 billion. Overall, weather-related catastrophe losses exceeded 0.4 percent of global GDP in 2017 (based on data from Aon Benfield, Munich Re and the World Bank), the second highest figure since 1990. In that period, only 2005 saw a higher relative catastrophe loss at around 0.5 percent of GDP.

But, it seems, (re)insurers were much better prepared to absorb major losses this time around. Much has changed in the 12 years since Hurricane Katrina breached the levees in New Orleans. Catastrophe modeling as a profession has evolved into exposure management, models and underlying data have improved and there is a much greater appreciation of model uncertainty and assumptions, explains Alan Godfrey, head of exposure management at Asta.

“Even post-2005 people would still see an event occurring, go to the models and pull out a single event ID … then tell all and sundry this is what we’re going to lose. And that’s an enormous misinterpretation of how the models are supposed to be used. In 2017, people demonstrated a much greater maturity and used the models to advise their own loss estimates, and not the other way around.”

It also helped that the industry was extremely well-capitalized moving into 2017. After a decade of operating through a low interest rate and increasingly competitive environment, (re)insurers had taken a highly disciplined approach to capital management. Gone are the days where a major event sparked a series of run-offs. While some (re)insurers have reported higher losses than others, all have emerged intact.

“In 2017 the industry has performed incredibly well from an operational point of view,” says Godfrey. “There have obviously been challenges from large losses and recovering capital, but those are almost outside of exposure management.”

According to Aon Benfield, global reinsurance capacity grew by 80 percent between 1990 and 2017 (to US$605 billion), against global GDP growth of around 24 percent. The influx of capacity from the capital markets into U.S. property catastrophe reinsurance has also brought about change and innovation, offering new instruments such as catastrophe bonds for transferring extreme risks.

Harvey broke all U.S. records for tropical cyclone-driven rainfall with observed cumulative rainfall of 51 inches

Much of this growth in non-traditional capacity has been facilitated by better data and more sophisticated analytics, along with a healthy appetite for insurance risk from pension funds and other institutional investors.

For insurance-linked securities (ILS), the 2017 North Atlantic hurricane season, Mexico’s earthquakes and California’s wildfires were their first big test. “Some thought that once we had a significant year that capital would leave the market,” says John Huff, president and chief executive of the Association of Bermuda Insurers and Reinsurance (ABIR). “And we didn’t see that.

“In January 2018 we saw that capital being reloaded,” he continues. “There is abundant capital in all parts of the reinsurance market. Deploying that capital with a reasonable rate of return is, of course, the objective.”

Huff thinks the industry performed extremely well in 2017 in spite of the severity of the losses and a few surprises. “I’ve even heard of reinsurers that were ready with claim payments on lower layers before the storm even hit. The modeling and ability to track the weather is getting more sophisticated. We saw some shifting of the storms — Irma was the best example — but reinsurers were tracking that in real time in order to be able to respond.”

The Buffalo Bayou River floods a park in Houston after the arrival of Hurricane Harvey

How Harvey Inundated Houston

One lesson the industry has learned over three decades of modeling is that models are approximations of reality. Each event has its own unique characteristics, some of which fall outside of what is anticipated by the models.

The widespread inland flooding that occurred after Hurricane Harvey made landfall on the Texas coastline is an important illustration of this, explains Huff. Even so, he adds, it continued a theme, with flood losses being a major driver of U.S. catastrophe claims for several years now. “What we’re seeing is flood events becoming the No. 1 natural disaster in the U.S. for people who never thought they were at risk of flood.”

Harvey broke all U.S. records for tropical cyclone-driven rainfall with observed cumulative rainfall of 51 inches (129 centimeters). The extreme rainfall generated by Harvey and the unprecedented inland flooding across southeastern Texas and parts of southern Louisiana was unusual.

However, nobody was overly surprised by the fact that losses from Harvey were largely driven by water versus wind. Prior events with significant storm surge-induced flooding, including Hurricane Katrina and 2012’s Superstorm Sandy, had helped to prepare (re)insurers, exposure managers and modelers for this eventuality. “The events themselves were very large but they were well within uncertainty ranges and not disproportionate to expectations,” says Godfrey.

“Harvey is a new data point — and we don’t have that many — so the scientists will look at it and know that any new data point will lead to tweaks,” he continues. “If anything, it will make people spend a bit more time on their calibration for the non-modeled elements of hurricane losses, and some may conclude that big changes are needed to their own adjustments.”

But, he adds: “Nobody is surprised by the fact that flooding post-hurricane causes loss. We know that now. It’s more a case of tweaking and calibrating, which we will be doing for the rest of our lives.”

Flood Modeling

Hurricane Harvey also underscored the importance of the investment in sophisticated, probabilistic flood models. RMS ran its U.S. Inland Flood HD Model in real time to estimate expected flood losses. “When Hurricane Harvey happened, we had already simulated losses of that magnitude in our flood model, even before the event occurred,” says Dr. Pete Dailey, vice president of product management and responsible for U.S. flood modeling at RMS.

“The value of the model is to be able to anticipate extreme tail events well before they occur, so that insurance companies can be prepared in advance for the kind of risk they’re taking on and what potential claims volume they may have after a major event,” he adds.

Does this mean that a US$100 billion-plus loss year like 2017 is now a 1-in-6-year event?

Harvey has already offered a wealth of new data that will be fed into the flood model. The emergency shutdown of the Houston metropolitan area prevented RMS meteorologists and engineers from accessing the scene in the immediate aftermath, explains Dailey. However, once on the ground they gathered as much information as they could, observing and recording what had actually happened to affected properties.

“We go to individual properties to assess the damage visually, record the latitude and longitude of the property, the street address, the construction, occupancy and the number of stories,” he says. “We will also make an estimate of the age of the property. Those basic parameters allow us to go back and take a look at what the model would have predicted in terms of damage and loss, as compared to what we observed.”

The fact that insured losses emanating from the flooding were only a fraction of the total economic losses is an inevitable discussion point. The majority of claims paid were for commercial properties, with residential properties falling under the remit of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Many residential homes were uninsured, however, explains ABIR’s Huff.

“The NFIP covers just the smallest amount of people — there are only five million policies — and yet you see a substantial event like Harvey which is largely uninsured because (re)insurance companies only cover commercial flood in the U.S.,” he says. “After Harvey you’ll see a realization that the private market is very well-equipped to get back into the private flood business, and there’s a national dialogue going on now.”

Is 2017 the New Normal?

One question being asked in the aftermath of the 2017 hurricane season is: What is the return period for a loss year like 2017? RMS estimates that, in terms of U.S. and Caribbean industry insured wind, storm surge and flood losses, the 2017 hurricane season corresponds to a return period between 15 and 30 years.

However, losses on the scale of 2017 occur more frequently when considering global perils. Adjusted for inflation, it is seven years since the industry paid out a similar level of catastrophe claims — US$110 billion on the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, Thai floods and New Zealand earthquake in 2011. Six years prior to that, KRW cost the industry in excess of US$75 billion (well over US$100 billion in today’s money).

So, does this mean that a US$100 billion-plus (or equivalent in inflation-adjusted terms) loss year like 2017 is now a one-in-six-year event? As wealth and insurance penetration grows in developing parts of the world, will we begin to see more loss years like 2011, where catastrophe claims are not necessarily driven by the U.S. or Japan peak zones?

“Increased insurance penetration does mean that on the whole losses will increase, but hopefully this is proportional to the premiums and capital that we are getting in,” says Asta’s Godfray. “The important thing is understanding correlations and how diversification actually works and making sure that is applied within business models.

“In the past, people were able to get away with focusing on the world in a relatively binary fashion,” he continues. “The more people move toward diversified books of business, which is excellent for efficient use of capital, the more important it becomes to understand the correlations between different regions.”

“You could imagine in the future, a (re)insurer making a mistake with a very sophisticated set of catastrophe and actuarial models,” he adds. “They may perfectly take into account all of the non-modeled elements but get the correlations between them all wrong, ending up with another year like 2011 where the losses across the globe are evenly split, affecting them far more than their models had predicted.”

As macro trends including population growth, increasing wealth, climate change and urbanization influence likely losses from natural catastrophes, could this mean a shorter return period for years like last year, where industry losses exceeded US$134 billion?

“When we look at the average value of properties along the U.S. coastline — the Gulf Coast and East Coast — there’s a noticeable trend of increasing value at risk,” says Dailey. “That is because people are building in places that are at risk of wind damage from hurricanes and coastal flooding. And these properties are of a higher value because they are more complex, have a larger square footage and have more stories. Which all leads to a higher total insured value.

“The second trend that we see would be from climate change whereby the storms that produce damage along the coastline may be increasing in frequency and intensity,” he continues. “That’s a more difficult question to get a handle on but there’s a building consensus that while the frequency of hurricane landfalls may not necessarily be increasing, those that do make landfall are increasing in intensity.”

Lloyd’s chief executive Inga Beale has stated her concerns about the impact of climate change, following the market’s £4.5 billion catastrophe claims bill for 2017. “That’s a significant number, more than double 2016; we’re seeing the impact of climate change to a certain extent, particularly on these weather losses, with the rising sea level that impacts and increases the amount of loss,” she said in an interview with Bloomberg.

While a warming climate is expected to have significant implications for the level of losses arising from storms and other severe weather events, it is not yet clear exactly how this will manifest, according to Tom Sabbatelli, senior product manager at RMS. “We know the waters have risen several centimeters in the last couple of decades and we can use catastrophe models to quantify what sort of impact that has on coastal flooding, but it’s also unclear what that necessarily means for tropical cyclone strength.

“The oceans may be warming, but there’s still an ongoing debate about how that translates into cyclone intensity, and that’s been going on for a long time,” he continues. “The reason for that is we just don’t know until we have the benefit of hindsight. We haven’t had a number of major hurricanes in the last few years, so does that mean that the current climate is quiet in the Atlantic? Is 2017 an anomaly or are we going back to more regular severe activity? It’s not until you’re ten or 20 years down the line and you look back that you know for sure.”