With many short-term reauthorizations of the National Flood Insurance Program, EXPOSURE considers how the private insurance market can bolster its presence in the U.S. flood arena and overcome some of the challenges it faces.

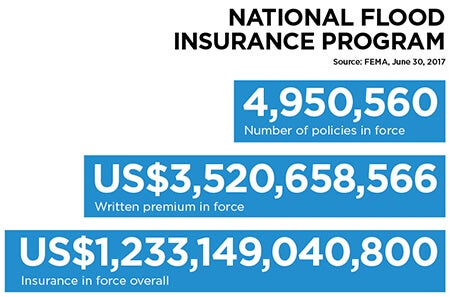

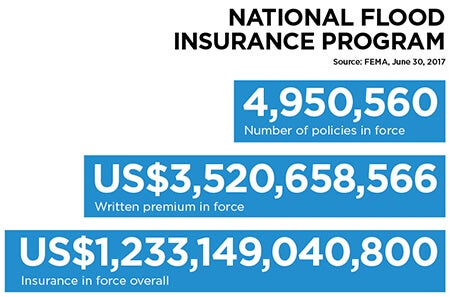

According to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), as of June 30, 2017, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) had around five million policies in force, representing a total in-force written premium exceeding US$3.5 billion and an overall exposure of about US$1.25 trillion. Florida alone accounts for over a third of those policies, with over 1.7 million in force in the state, representing premiums of just under US$1 billion.

However, with the RMS Exposure Source Database estimating approximately 85 million residential properties alone in the U.S., the NFIP only encompasses a small fraction of the overall number of properties exposed to flood, considering floods can occur throughout the country.

Factors limiting the reach of the program have been well documented: the restrictive scope of NFIP policies, the fact that mandatory coverage applies only to special flood hazard plains, the challenges involved in securing elevation certificates, the cost and resource demands of conducting on-site inspections, the poor claims performance of the NFIP, and perhaps most significant the refusal by many property owners to recognize the threat posed by flooding.

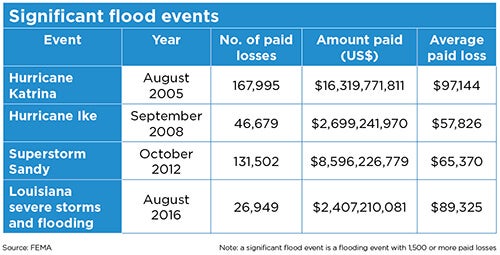

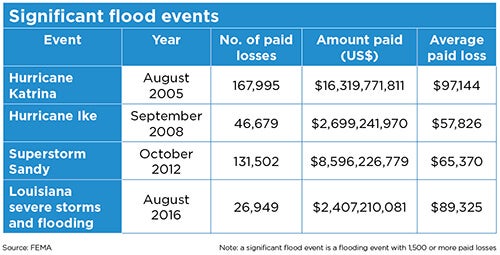

At the time of writing, the NFIP is once again being put to the test as Hurricane Harvey generates catastrophic floods across Texas. As the affected regions battle against these unprecedented conditions, it is highly likely that the resulting major losses will add further impetus to the push for a more substantive private flood insurance market.

The Private Market Potential

While the private insurance sector shoulders some of the flood coverage, it is a drop in the ocean, with RMS estimating the number of private flood policies to be around 200,000. According to Dan Alpay, line underwriter for flood and household at Hiscox London Market, private insurers represent around US$300 to US$400 million of premium — although he adds that much of this is in “big- ticket policies” where flood has been included as part of an all-risks policy.

“In terms of stand-alone flood policies,” he says, “the private market probably only represents about US$100 million in premiums — much of which has been generated in the last few years, with the opening up of the flood market following the introduction of the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 and the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014.”

But it is clear therefore that the U.S. flood market represents one of the largest untapped insurance opportunities in the developed world, with trillions of dollars of property value at risk across the country.

“It is extremely rare to have such a huge potential market like this,” says Alpay, “and we are not talking about a risk that the market does not understand. It is U.S. catastrophe business, which is a sector that the private market has extensive experience in. And while most insurers have not provided specific cover for U.S. flood before, they have been providing flood policies in many other countries for many years, so have a clear understanding of the peril characteristics. And I would also say that much of the experience gained on the U.S. wind side is transferable to the flood sector.”

Yet while the potential may be colossal, the barriers to entry are also significant. First and foremost, there is the challenge of going head-to-head with the NFIP itself. While there is concerted effort on the part of the U.S. government to facilitate a greater private insurer presence in the flood market as part of its reauthorization, the program has presided over the sector for almost 50 years and competing for those policies will be no easy task.

“The main problem is changing consumer behavior,” believes Alpay. “How do we get consumers who have been buying policies through the NFIP since 1968 to appreciate the value of a private market product and trust that it will pay out in the event of a loss? While you may be able to offer a product that on paper is much more comprehensive and provides a better deal for the insured, many will still view it as risky given their inherent trust in the government.”

For many companies, the aim is not to compete with the program, but rather to source opportunities beyond the flood zones, accessing the potential that exists outside of the mandatory purchase requirements. But to do this, property owners who are currently not located in these zones need to understand that they are actually in an at-risk area and need to consider purchasing flood cover. This can be particularly challenging in locations where homeowners have never experienced a damaging flood event.

Another market opportunity lies in providing coverage for large industrial facilities and high-value commercial properties, according to Pete Dailey, vice president of product management at RMS. “Many businesses already purchase NFIP policies,” he explains, “in fact those with federally insured mortgages and locations in high-risk flood zones are required to do so.

“However,” he continues, “most businesses with low-to-moderate flood risk are unaware that their business policy excludes flood damage to the building, its contents and losses due to business interruption. Even those with NFIP coverage have a US$500,000 limit and could benefit from an excess policy. Insurers eager to expand their books by offering new product options to the commercial lines will facilitate further expansion of the private market.”

Assessing the Flood Level

But to be able to effectively target this market, insurers must first be able to ascertain what the flood exposure levels really are. The current FEMA flood mapping database spans 20,000 individual plains. However, much of this data is out of date, reflecting limited resources, which, coupled with a lack of consistency in how areas have been mapped using different contractors, means their risk assessment value is severely limited.

While a proposal to use private flood mapping studies instead of FEMA maps is being considered, the basic process of maintaining flood plain data is an immense problem given the scale. With the U.S. exposed to flood in virtually every location, this makes it a high-resolution peril, meaning there is a long list of attributes and inter-dependent dynamic factors influencing what flood risk in a particular area might be. With 100 years of scientific research, the physics of flooding itself is well understood, the issue has been generating the data and creating the model at sufficient resolution to encompass all of the relevant factors from an insurance perspective.

In fact, to manage the scope of the data required to release the RMS U.S. Flood Hazard Maps for a small number of return periods required the firm to build a supercomputer, capitalizing on immense Cloud-based technology to store and manage the colossal streams of information effectively.

With such data now available, insurers are in a much better position to generate functional underwriting maps – FEMA maps were never drawn up for underwriting purposes. The new hazard maps provide actual gradient and depth of flooding data, to get away from the ‘in’ or ‘out’ discussion, allowing insurers to provide detail, such as if a property is exposed to two to three feet of flooding at a 1-in-100 return period.

No Clear Picture

Another hindrance to establishing a clear flood picture is the lack of a systematic database of the country’s flood defense network. RMS estimates that the total network encompasses some 100,000 miles of flood defenses; however, FEMA’s levy network accounts for approximately only 10 percent of this. Without the ability to model existing flood defenses accurately, higher frequency, lower risk events are overestimated.

To help counter this lack of defense data, RMS developed the capability within its U.S. Inland Flood HD Model to identify the likelihood of such measures being present and, in turn, assess the potential protection levels. Data shortage is also limiting the potential product spectrum. If an insurer is not able to demonstrate to a ratings agency or regulator what the relationship between different sources of flood risk (such as storm surge and river flooding) is for a given portfolio, then it could reduce the range of flood products they can offer. Insurers also need the tools and the data to differentiate the more complicated financial relationships, exclusions and coverage options relative to the nature of the events that could occur.

Launching into the Sector

In May 2016, Hiscox London Market launched its FloodPlus product into the U.S. homeowners sector, following the deregulation of the market. Distributed through wholesale brokers in the U.S., the policy is designed to offer higher limits and a wider scope than the NFIP.

“We initially based our product on the NFIP policy with slightly greater coverage,” Alpay explains, “but we soon realized that to firmly establish ourselves in the market we had to deliver a policy of sufficient value to encourage consumers to shift from the NFIP to the private market.

“As we were building the product and setting the limits,” he continues, “we also looked at how to price it effectively given the lack of granular flood information. We sourced a lot of data from external vendors in addition to proprietary modeling which we developed ourselves, which enabled us to build our own pricing system. What that enabled us to do was to reduce the process time involved in buying and activating a policy from up to 30 days under the NFIP system to a matter of minutes under FloodPlus.” This sort of competitive edge will help incentivize NFIP policyholders to make a switch.

“We also conducted extensive market research through our coverholders,” he adds, “speaking to agents operating within the NFIP system to establish what worked and what didn’t, as well as how claims were handled.”

“We soon realized that to firmly establish ourselves … we had to deliver a policy of sufficient value to encourage consumers to shift from the NFIP to the private market”

Dan Alpay

Hiscox London Market

Since launch, the product has been amended on three occasions in response to customer demand. “For example, initially the product offered actual cash value on contents in line with the NFIP product,” he adds. “However, after some agent feedback, we got comfortable with the idea of providing replacement cost settlement, and we were able to introduce this as an additional option which has proved successful.”

To date, coverholder demand for the product has outstripped supply, he says. “For the process to work efficiently, we have to integrate the FloodPlus system into the coverholder’s document issuance system. So, given the IT integration process involved plus the education regarding the benefits of the product, it can’t be introduced too quickly if it is to be done properly.” Nevertheless, growing recognition of the risk and the need for coverage is encouraging to those seeking entry into this emerging market.

A Market in the Making

The development of a private U.S. flood insurance market is still in its infancy, but the wave of momentum is building.

Lack of relevant data, particularly in relation to loss history, is certainly dampening the private sector’s ability to gain market traction. However, as more data becomes available, modeling capabilities improve, and insurer products gain consumer trust by demonstrating their value in the midst of a flood event, the market’s potential will really begin to flow.

“Most private insurers,” concludes Alpay, “are looking at the U.S. flood market as a great opportunity to innovate, to deliver better products than those currently available, and ultimately to give the average consumer more coverage options than they have today, creating an environment better for everyone involved.” The same can be said for the commercial and industrial lines of business where stakeholders are actively searching for cost savings and improved risk management.

Climate Complications

As the private flood market emerges, so too does the debate over how flood risk will adjust to a changing climate. “The consensus today among climate scientists is that climate change is real and that global temperatures are indeed on the rise,” says Pete Dailey, vice president of product management at RMS. “Since warmer air holds more moisture, the natural conclusion is that flood events will become more common and more severe. Unfortunately, precipitation is not expected to increase uniformly in time or space, making it difficult to predict where flood risk would change in a dramatic way.”

Further, there are competing factors that make the picture uncertain. “For example,” he explains, “a warmer environment can lead to reduced winter snowpack, and, in turn, reduced springtime melting. Thus, in regions susceptible to springtime flooding, holding all else constant, warming could potentially lead to reduced flood losses.”

For insurers, these complications can make risk selection and portfolio management more complex. “While the financial implications of climate change are uncertain,” he concludes, “insurers and catastrophe modelers will surely benefit from climate change research and byproducts like better flood hazard data, higher resolution modeling and improved analytics being developed by the climate science community.”