Marleen Nyst and Nilesh Shome of RMS explore some of the lessons and implications from the recent sequence of earthquakes in California

On the morning of July 4, 2019, the small town of Ridgecrest in California’s Mojave Desert unexpectedly found itself at the center of a major news story after a magnitude 6.4 earthquake occurred close by. This earthquake later transpired to be a foreshock for a magnitude 7.1 earthquake the following day, the strongest earthquake to hit the state for 20 years.

On the morning of July 4, 2019, the small town of Ridgecrest in California’s Mojave Desert unexpectedly found itself at the center of a major news story after a magnitude 6.4 earthquake occurred close by. This earthquake later transpired to be a foreshock for a magnitude 7.1 earthquake the following day, the strongest earthquake to hit the state for 20 years.

These events, part of a series of earthquakes and aftershocks that were felt by millions of people across the state, briefly reignited awareness of the threat posed by earthquakes in California. Fortunately, damage from the Ridgecrest earthquake sequence was relatively limited. With the event not causing a widespread social or economic impact, its passage through the news agenda was relatively swift.

But there are several reasons why an event such as the Ridgecrest earthquake sequence should be a focus of attention both for the insurance industry and the residents and local authorities in California.

“If Ridgecrest had happened in a more densely populated area, this state would be facing a far different economic future than it is today”

Glenn Pomeroy

California Earthquake Authority

“We don’t want to minimize the experiences of those whose homes or property were damaged or who were injured when these two powerful earthquakes struck, because for them these earthquakes will have a lasting impact, and they face some difficult days ahead,” explains Glenn Pomeroy, chief executive of the California Earthquake Authority.

“However, if this series of earthquakes had happened in a more densely populated area or an area with thousands of very old, vulnerable homes, such as Los Angeles or the San Francisco Bay Area, this state would be facing a far different economic future than it is today — potentially a massive financial crisis,” Pomeroy says.

Although one of the most populous U.S. states, California’s population is mostly concentrated in metropolitan areas. A major earthquake in one of these areas could have repercussions for both the domestic and international economy.

Low Probability, High Impact

Earthquake is a low probability, high impact peril. In California, earthquake risk awareness is low, both within the general public and many (re)insurers. The peril has not caused a major insured loss for 25 years, the last being the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake in 1994.

California earthquake has the potential to cause large-scale insured and economic damage. A repeat of the Northridge event would likely cost the insurance industry today around US$30 billion, according to the latest version of the RMS® North America Earthquake Models, and Northridge is far from a worst-case scenario.

From an insurance perspective, one of the most significant earthquake events on record would be the magnitude 9.0 Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011. For California, the 1906 magnitude 7.8 San Francisco earthquake, when Lloyd’s underwriter Cuthbert Heath famously instructed his San Franciscan agent to “pay all of our policyholders in full, irrespective of the terms of their policies”, remains historically significant.

Heath’s actions led to a Lloyd’s payout of around US$50 million at the time and helped cement Lloyd’s reputation in the U.S. market. RMS models suggest a repeat of this event today could cost the insurance industry around US$50 billion.

But the economic cost of such an event could be around six times the insurance bill — as much as US$300 billion — even before considering damage to infrastructure and government buildings, due to the surprisingly low penetration of earthquake insurance in the state.

Events such as the 1906 earthquake and even Northridge are too far in the past to remain in public consciousness. And the lack of awareness of the peril’s damage potential is demonstrated by the low take-up of earthquake insurance in the state.

“Because large, damaging earthquakes don’t happen very frequently, and we never know when they will happen, for many people it’s out of sight, out of mind. They simply think it won’t happen to them,” Pomeroy says.

Across California, an average of just 12 percent to 14 percent of homeowners have earthquake insurance. Take-up varies across the state, with some high-risk regions, such as the San Francisco Bay Area, experiencing take-up below the state average. Take-up tends to be slightly higher in Southern California and is around 20 percent in Los Angeles and Orange counties.

Take-up will typically increase in the aftermath of an event as public awareness rises but will rapidly fall as the risk fades from memory. As with any low probability, high impact event, there is a danger the public will not be well prepared when a major event strikes.

The insurance industry can take steps to address this challenge, particularly through working to increase awareness of earthquake risk and actively promoting the importance of having insurance coverage for faster recovery. RMS and its insurance partners have also been working to improve society’s resilience against risks such as earthquake, through initiatives such as the 100 Resilient Cities program.

Understanding the Risk

While the tools to model and understand earthquake risk are improving all the time, there remain several unknowns which underwriters should be aware of. One of the reasons the Ridgecrest Earthquake came as such a surprise was that the fault on which it occurred was not one that seismologists knew existed.

Several other recent earthquakes — such as the 2014 Napa event, the Landers and Big Bear Earthquakes in 1992, and the Loma Prieta Earthquake in 1989 — took place on previously unknown or thought to be inactive faults or fault strands. As well as not having a full picture of where the faults may lie, scientific understanding of how multifaults can link together to form a larger event is also changing.

Events such as the Kaikoura Earthquake in New Zealand in 2016 and the Baja California Earthquake in Mexico in 2010 have helped inform new scientific thinking that faults can link together causing more damaging, larger magnitude earthquakes. The RMS North America Earthquake Models have also evolved to factor in this thinking and have captured multifault ruptures in the model based on the latest research results. In addition, studying the interaction between the faults that ruptured in the Ridgecrest events will allow RMS to improve the fault connectivity in the models.

A further learning from New Zealand came via the 2011 Christchurch Earthquake, which demonstrated how liquefaction of soil can be a significant loss driver due to soil condition in certain areas. The San Francisco Bay Area, an important national and international economic hub, could suffer a similar impact in the event of a major earthquake. Across the area, there has been significant residential and commercial development on artificial landfill areas over the last 100 years, which are prone to have significant liquefaction damage, similar to what was observed in Christchurch.

Location, Location, Location

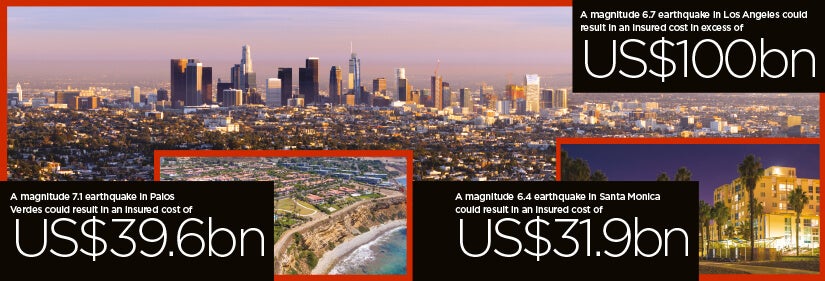

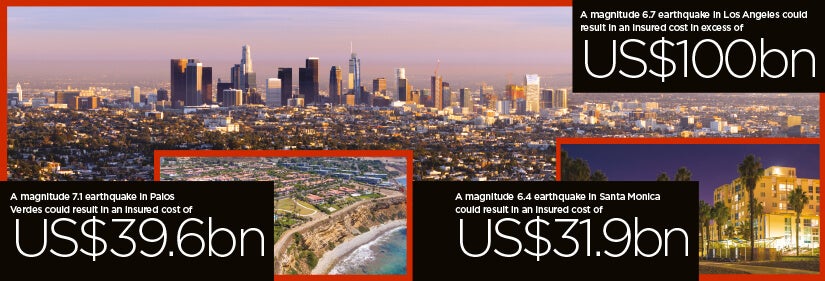

Clearly, the location of the earthquake is critical to the scale of damage and insured and economic impact from an event. Ridgecrest is situated roughly 200 kilometers north of Los Angeles. Had the recent earthquake sequence occurred beneath Los Angeles instead, then it is plausible that the insured cost could have been in excess of US$100 billion.

The Puente Hills Fault, which sits underneath downtown LA, wasn’t discovered until around the turn of the century. A magnitude 6.8 Puente Hills event could cause an insured loss of US$78.6 billion, and a Newport-Inglewood magnitude 7.3 would cost an estimated US$77.1 billion according to RMS modeling. These are just a couple of the examples within its stochastic event set with a similar magnitude to the Ridgecrest events and which could have a significant social, economic and insured loss impact if they took place elsewhere in the state.

The RMS model estimates that magnitude 7 earthquakes in California could cause insurance industry losses ranging from US$20,000 to a US$20 billion, but the maximum loss could be over US$100 billion if occurring in high population centers such as Los Angeles. The losses from the Ridgecrest event were on the low side of the range of loss as the event occurred in a less populated area. For the California Earthquake Authority’s portfolio in Los Angeles County, a large loss event of US$10 billion or greater can be expected approximately every 30 years.

As with any major catastrophe, several factors can drive up the insured loss bill, including post-event loss amplification and contingent business interruption, given the potential scale of disruption. In Sacramento, there is also a risk of failure of the levee system.

Fire following earthquake was a significant cause of damage following the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and was estimated to account for around 40 percent of the overall loss from that event. It is, however, expected that fire would make a much smaller contribution to future events, given modern construction materials and methods and fire suppressant systems.

Political pressure to settle claims could also drive up the loss total from the event. Lawmakers could put pressure on the CEA and other insurers to settle claims quickly, as has been the case in the aftermath of other catastrophes, such as Hurricane Sandy.

The California Earthquake Authority has recommended homes built prior to 1980 be seismically retrofitted to make them less vulnerable to earthquake damage. “We all need to learn the lesson of Ridgecrest: California needs to be better prepared for the next big earthquake because it’s sure to come,” Pomeroy says.

“We recommend people consider earthquake insurance to protect themselves financially,” he continues. “The government’s not going to come in and rebuild everybody’s home, and a regular residential insurance policy does not cover earthquake damage. The only way to be covered for earthquake damage is to have an additional earthquake insurance policy in place.

“Close to 90 percent of the state does not have an earthquake insurance policy in place. Let this be the wake-up call that we all need to get prepared.”

On the morning of July 4, 2019, the small town of Ridgecrest in California’s Mojave Desert unexpectedly found itself at the center of a major news story after a magnitude 6.4 earthquake occurred close by. This earthquake later transpired to be a foreshock for a magnitude 7.1 earthquake the following day, the strongest earthquake to hit the state for 20 years.

On the morning of July 4, 2019, the small town of Ridgecrest in California’s Mojave Desert unexpectedly found itself at the center of a major news story after a magnitude 6.4 earthquake occurred close by. This earthquake later transpired to be a foreshock for a magnitude 7.1 earthquake the following day, the strongest earthquake to hit the state for 20 years.