China has made strong progress in developing agricultural insurance and aims to continually improve. As farming practices evolve, and new capabilities and processes enhance productivity, how can agricultural insurance in China keep pace with trending market needs? EXPOSURE investigates.

The People’s Republic of China is a country of immense scale. Covering some 9.6 million square kilometers (3.7 million square miles), just two percent smaller than the U.S., the region spans five distinct climate areas with a diverse topography extending from the lowlands to the east and south to the immense heights of the Tibetan Plateau.

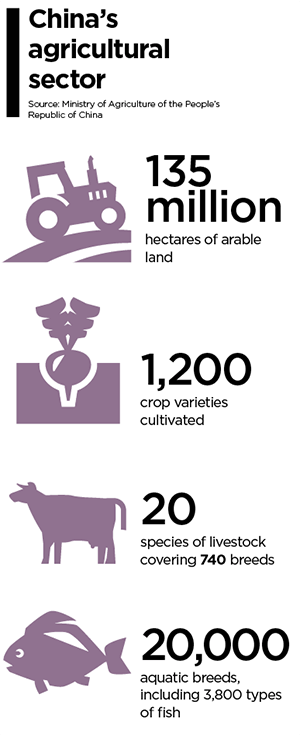

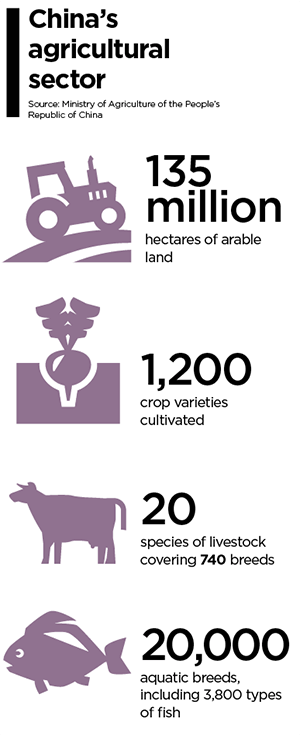

Arable land accounts for approximately 135 million hectares (521,238 square miles), close to four times the size of Germany, feeding a population of 1.3 billion people. In total, over 1,200 crop varieties are cultivated, ranging from rice and corn to sugar cane and goji berries. In terms of livestock, some 20 species covering over 740 breeds are found across China; while it hosts over 20,000 aquatic breeds, including 3,800 types of fish.1

A Productive Approach

With per capita land area less than half of the global average, maintaining agricultural output is a central function of the Chinese government, and agricultural strategy has formed the primary focus of the country’s “No. 1 Document” for the last 14 years.

To encourage greater efficiency, the central government has sought to modernize methods and promote large-scale production, including the creation of more agriculture cooperatives, including a doubling of agricultural machinery cooperatives encouraging mechanization over the last four years.2 According to the Ministry of Agriculture, by the end of May 2015 there were 1.393 million registered farming cooperatives, up 22.4 percent from 2014 — a year that saw the government increase its funding for these specialized entities by 7.5 percent to ¥2 billion (US$0.3 billion).

Changes in land allocation are also dramatically altering the landscape. In April 2017, the minister of agriculture, Han Changfu, announced plans to assign agricultural production areas to two key functions over the next three years, with 900 million mu (60 million hectares) for primary grain products, such as rice and wheat, and 238 million mu (16 million hectares) for five other key products, including cotton, rapeseed and natural rubber.

Productivity levels are also being boosted by enhanced farming techniques and higher-yield crops, with new varieties of crop including high-yield wheat and “super rice” increasing annual tonnage. Food grain production has risen from 446 million tons in 1990 to 621 million tons in 2015.3 The year 2016 saw a 0.8 percent decline — the first in 12 years — but structural changes were a contributory factor.

Insurance Penetration

China is one of the most exposed regions in the world to natural catastrophes. Historically, China has repeatedly experienced droughts with different levels of spatial extent of damage to crops, including severe widespread droughts in 1965, 2000 and 2007. Frequent flooding also occurs, but with development of flood mitigation schemes, flooding of crop areas is on a downward trend. China has, however, borne the brunt of one the costliest natural catastrophes to date in 2017, according to Aon Benfield,4 with July floods along the Yangtze River basin causing economic losses topping US$6.4 billion. The 2016 summer floods caused some US$28 billion in losses along the river;5 while flooding in northeastern China caused a further US$4.7 billion in damage. Add drought losses of US$6 billion and the annual weather-related losses stood at US$38.7 billion.6 However, insured losses are a fraction of that figure, with only US$1.1 billion of those losses insured.

“Often companies not only do not know where their exposures are, but also what the specific policy requirements for that particular region are in relation to terms and conditions”

Laurent Marescot

RMS

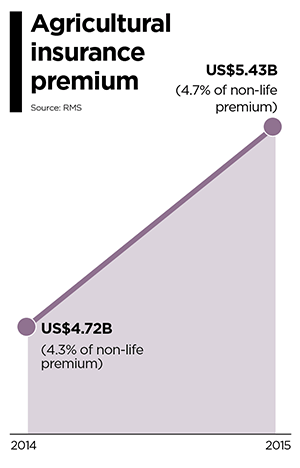

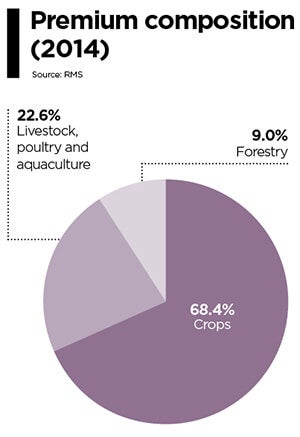

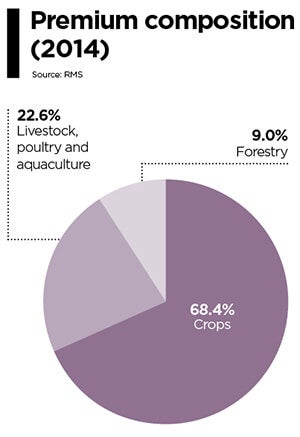

The region represents the world’s second largest agricultural insurance market, which has grown from a premium volume of US$100 million in 2006 to more than US$6 billion in 2016. However, government subsidies — at both central and local level — underpin the majority of the market. In 2014, the premium subsidy level ranged from between 65 percent and 80 percent depending on the region and the type of insurance.

Most of the insured are small acreage farms, for which crop insurance is based on a named peril but includes multiple peril cover (drought, flood, extreme winds and hail, freeze and typhoon). Loss assessment is generally performed by surveyors from the government, insurers and an individual that represents farmers within a village. Subsidized insurance is limited to specific crop varieties and breeds and primarily covers only direct material costs, which significantly lowers its appeal to the farming community.

One negative impact of current multi-peril crop insurance is the cost of operations, thus reducing the impact of subsidies. “Currently, the penetration of crop insurance in terms of the insured area is at about 70 percent,” says Mael He, head of agriculture, China, at Swiss Re. “However, the coverage is limited and the sum insured is low. The penetration is only 0.66 percent in terms of premium to agricultural GDP. As further implementation of land transfer in different provinces and changes in supply chain policy take place, livestock, crop yield and revenue insurance will be further developed.”

As He points out, changing farming practices warrant new types of insurance. “For the cooperatives, their insurance needs are very different compared to those of small household farmers. Considering their main income is from farm production, they need insurance cover on yield or event-price-related agricultural insurance products, instead of cover for just production costs in all perils.”

At Ground Level

Given low penetration levels and limited coverage, China’s agricultural market is clearly primed for growth. However, a major hindering factor is access to relevant data to inform meaningful insurance decisions. For many insurers, the time series of insurance claims is short, government-subsidized agriculture insurance only started in 2007, according to Laurent Marescot, senior director, market and product specialists at RMS.

“This a very limited data set upon which to forecast potential losses,” says Marescot. “Given current climate developments and changing weather patterns, it is highly unlikely that during that period we have experienced the most devastating events that we are likely to see. It is hard to get any real understanding of a potential 1-in-100 loss from such data.”

Major changes in agricultural practices also limit the value of the data. “Today’s farming techniques are markedly different from 10 years ago,” states Marescot. “For example, there is a rapid annual growth rate of total agricultural machinery power in China, which implies significant improvement in labor and land productivity.”

Insurers are primarily reliant on data from agriculture and finance departments for information, says He. “These government departments can provide good levels of data to help insurance companies understand the risk for the current insurance coverage. However, obtaining data for cash crops or niche species is challenging.”

“You also have to recognize the complexities in the data,” Marescot believes. “We accessed over 6,000 data files with government information for crops, livestock and forestry to calibrate our China Agricultural Model (CAM). Crop yield data is available from the 1980s, but in most cases it has to be calculated from the sown area. The data also needs to be processed to resolve inconsistencies and possibly de-trended, which is a fairly complex process. In addition, the correlation between crop yield and loss is not great as loss claims are made at a village level and usually involve negotiation.”

A Clear Picture

Without the right level of data, international companies operating in these territories may not have a clear picture of their risk profile.

“Often companies not only have a limited view where their exposures are, but also of what the specific policy requirements for that particular province are in relation to terms and conditions,” says Marescot. “These are complex as they vary significantly from one line of business and province to the next.”

A further level of complexity stems from the fact that not only can data be hard to source, but in many instances it is not reported on the same basis from province to province. This means that significant resource must be devoted to homogenizing information from multiple different data streams.

“We’ve devoted a lot of effort to ensuring the homogenization of all data underpinning the CAM,” Marescot explains. “We’ve also translated the information and policy requirements from Mandarin into English. This means that users can either enter their own policy conditions into the model or rely upon the database itself. In addition, the model is able to disaggregate low-resolution exposure to higher-resolution information, using planted area data information. All this has been of significant value to our clients.”

The CAM covers all three lines of agricultural insurance — crop, livestock and forestry. A total of 12 crops are modeled individually, with over 60 other crop types represented in the model. For livestock, CAM covers four main perils: disease, epidemics, natural disasters and accident/fire for cattle, swine, sheep and poultry.

The Technology Age

As efforts to modernize farming practices continue, so new technologies are being brought to bear on monitoring crops, mapping supply and improving risk management.

“More farmers are using new technology, such as apps, to track the growing conditions of crops and livestock and are also opening this to end consumers so that they can also monitor this online and in real-time,” He says. “There are some companies also trying to use blockchain technology to track the movements of crops and livestock based on consumer interest; for instance, from a piglet to the pork to the dumpling being consumed.”

He says, “3S technology — geographic information sciences, remote sensing and global positioning systems — are commonly used in China for agriculture claims assessments. Using a smartphone app linked to remote control CCTV in livestock farms is also very common. These digital approaches are helping farmers better manage risk.” Insurer Ping An is now using drones for claims assessment.

There is no doubt that as farming practices in China evolve, the potential to generate much greater information from new data streams will facilitate the development of new products better designed to meet on-the-ground requirements.

He concludes: “China can become the biggest agricultural insurance market in the next 10 years. … As the Chinese agricultural industry becomes more professional, risk management and loss assessment experience from international markets and professional farm practices could prove valuable to the Chinese market.”

References:

1. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China

2. Cheng Fang, “Development of Agricultural Mechanization in China,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, https://forum2017.iamo.de/microsites/forum2017.iamo.de/fileadmin/presentations/B5_Fang.pdf

3. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China

4. Aon Benfield, “Global Catastrophe Recap: First Half of 2017,” July 2017, http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/201707-if-1h-global-recap.pdf

5. Aon Benfield, “2016 Annual Global Climate and Catastrophe Report,” http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/20170117-ab-ifannualclimate-catastrophe-report.pdf

6. Ibid.

The Disaster Plan

In April 2017, China announced the launch of an expansive disaster insurance program spanning approximately 200 counties in the country’s primary grain producing regions, including Hebei and Anhui.

The program introduces a new form of agriculture insurance designed to provide compensation for losses to crop yields resulting from natural catastrophes, including land fees, fertilizers and crop-related materials.

China’s commitment to providing robust disaster cover was also demonstrated in 2016, when Swiss Re announced it had entered into a reinsurance protection scheme with the government of Heilongjiang Province and the Sunlight Agriculture Mutual Insurance Company of China — the first instance of the Chinese government capitalizing on a commercial program to provide cover for natural disasters.

The coverage provides compensation to farming families for both harm to life and damage to property as well as income loss resulting from floods, excessive rain, drought and low temperatures. It determines insurance payouts based on triggers from satellite and meteorological data.

Speaking at the launch, Swiss Re president for China John Chen said: “It is one of the top priorities of the government bodies in China to better manage natural catastrophe risks, and it has been the desire of the insurance companies in the market to play a bigger role in this sector. We are pleased to bridge the cooperation with an innovative solution and would look forward to replicating the solutions for other provinces in China.”