Reconnaissance work is built into the earthquake modeler’s job description – the backpack is always packed and ready. Large earthquakes are thankfully infrequent, but when they do occur, there is much to be learned from studying their impact, and this knowledge helps to improve risk models.

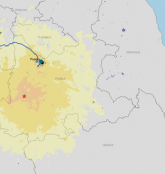

An RMS reconnaissance team recently visited Ecuador. Close to 7pm local time, on April 16, 2016, an Mw7.8 earthquake struck between the small towns of Muisne and Pedernales on the northwestern coast of Ecuador. Two smaller, more recent earthquakes have also impacted the area, on July 11, 2016 an Mw5.8 and Mw6.2, fortunately with no significant damage.

April’s earthquake was the strongest recorded in the country since 1979 and, at the time of writing, the strongest earthquake experienced globally so far in 2016. The earthquake caused more than 650 fatalities, more than 17,600 injuries, and damage to more than 10,000 buildings.

Two weeks after the earthquake, an RMS reconnaissance team of engineers started their work, visiting five cities across the affected region, including Guayaquil, Manta, Bahía de Caráquez, Pedernales, and Portoviejo. Pedernales was the most affected, experiencing the highest damage levels due to its proximity to the epicenter, approximately 40km to the north of the city.

Sharing the Same Common Vulnerability

The majority of buildings in the affected region were constructed using the same structural system: reinforced concrete (RC) frames with unreinforced concrete masonry (URM) infill. This type of structural system relies on RC beams and columns to resist earthquake shaking, with the walls filled in with unreinforced masonry blocks. This system was common across residential, industrial, and commercial properties and across occupancies, from hospitals and office buildings to government buildings and high-rise condominiums.

URM infill is particularly susceptible to damage during earthquakes, and for this reason it is prohibited by many countries with high seismic hazard. But even though Ecuador’s building code was updated in 2015, URM infill walls are still permitted in construction, and are even used in high-end residential and commercial properties.

Without reinforcing steel or adequate connection to the surrounding frame, the URM often cracks and crumbles during strong earthquake shaking. In some cases, damaged URM on the exterior of buildings falls outward, posing safety risks to people below. And for URM that falls inward, besides posing a safety risk, it often causes damage to interior finishes, mechanical equipment, and contents.

Across the five cities, the observed damage ranged from Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) 7.0-9.0. For an MMI of 7.0, the damage equated to light to moderate damage of URM infill walls, and mostly minimal damage to RC frames with isolated instances of moderate-to-heavy damage or collapse. An MMI of 9.0, which based on RMS observations, occurred in limited areas, meant moderate to heavy damage of URM infill walls and slight to severe damage or collapse to RC frames.

While failure of URM infill was the most common damage pattern observed, there were instances of partial and even complete structural collapse. Collapse was often caused, at least in part by poor construction materials and building configurations, such as vertical irregularities, that concentrated damage in particular areas of buildings.

Disruption to Business and Public Services

The RMS team also examined disruption to business and public services caused by the earthquake. A school in Portoviejo will likely be out of service for more than six months, and a police station in Pedernales will likely require more than a year of repair work. The disruption observed by the RMS team was principally due to direct damage to buildings and contents. However, there was some disruption to lifeline utilities such as electricity and water in the affected region, and this undoubtedly impacted some businesses.

RMS engineers also visited four public hospitals and clinics, with damage ranging from light to complete collapse. The entire second floor of a clinic in Portoviejo collapsed. A staff doctor told RMS that the floor was empty at the time and all occupants, including patients, evacuated safely.

Tourism was disrupted, with a few hotels experiencing partial or complete collapse. In some cases, even lightly damaged and unaffected hotels were closed as they were within cordoned-off zones in Manta or Portoviejo.

Tuna is an important export product for Ecuador. Two plants visited sustained minor structural damage, with unanchored machinery requiring repositioning and recalibration. One tuna processing plant reached 100% capacity just 16 days after the earthquake. Another in Manta reached 85% capacity about 17 days after the earthquake, and full capacity was expected within one month.

The need for risk differentiation

Occupancy, construction class, year built, and other building characteristics influence the vulnerability of buildings and, consequently, the damage they sustain during earthquakes. Vulnerability is so important in calculating damage from earthquakes that RMS model developers go to great lengths to ensure that each country’s particular engineering and construction practices are accurately captured by the models. This approach enables the models to differentiate risk across thousands of different factors.

Residential insurance penetration in Ecuador is still relatively low for commercial buildings and privately owned or financed homes, but higher amongst government-backed mortgages, as these require insurance. The knowledge gained from reconnaissance work is fundamental to our understanding of earthquake risk and informs future updates to RMS models. Better models will improve the insurance industry’s understanding and management of earthquake risk as insurance penetration increases both here and around the world.