The North Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30 but based on the large exposure the (re)insurance industry has to hurricanes, intrigue about what each season will deliver persists year-round. And with three months to go until the official start of the 2019 season, (re)insurers and catastrophe modelers are actively looking ahead to see what it might deliver.

Although the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) does not issue its annual seasonal activity forecasts before late May, others in the meteorological community do provide early indications of upcoming activity. These started as early as December last year with forecasts and commentary issued by Tropical Storm Risk (TSR) and Colorado State University (CSU). But how skillful are these extended range forecasts and what insight, if any, can we gain from them?

What are the Extended Range Forecasts Suggesting for 2019?

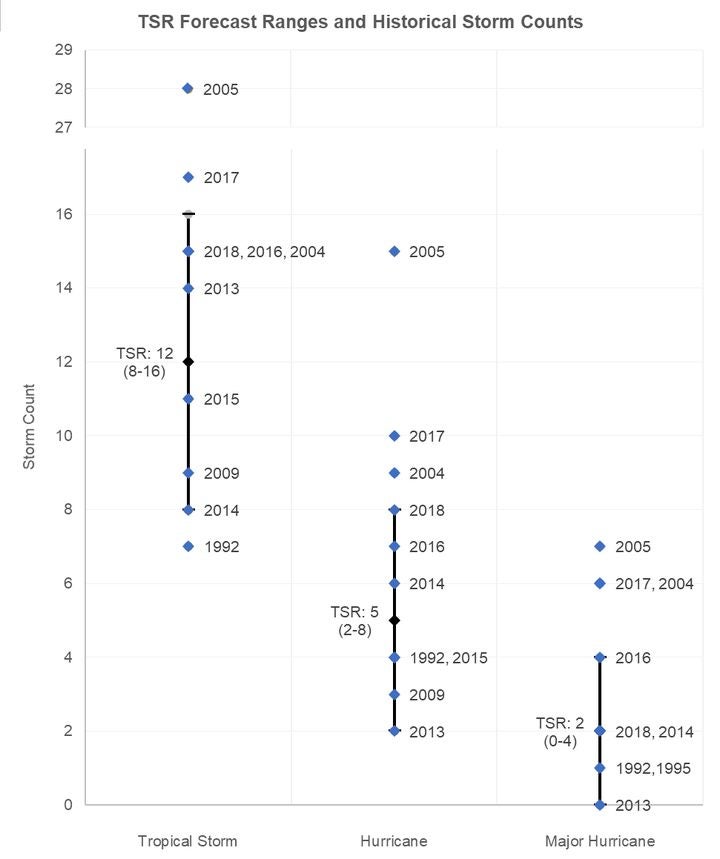

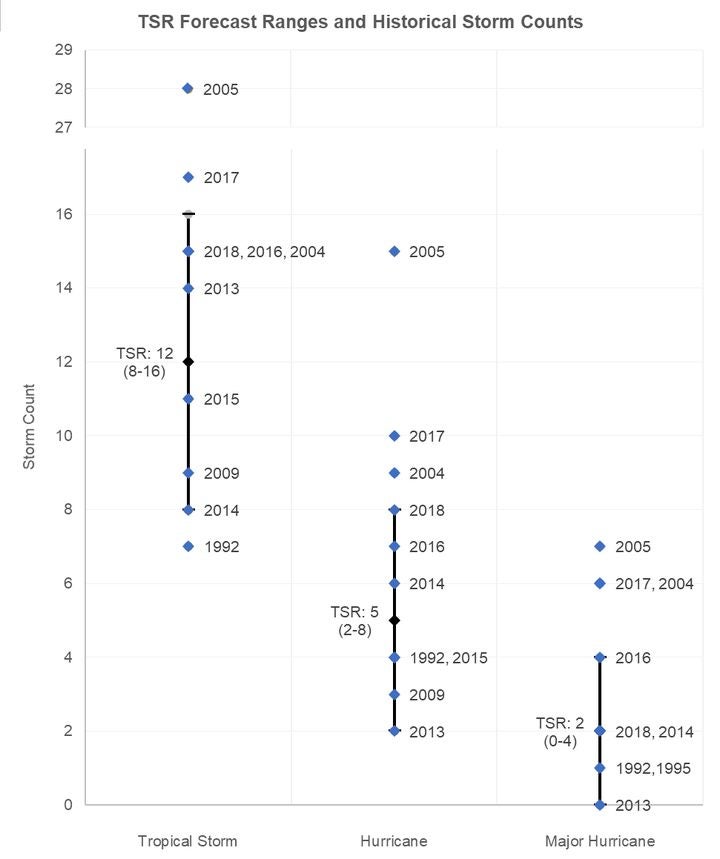

In its first 2019 season outlook, TSR predicted that this year’s activity will be slightly below the long-term average, and calls for 12 tropical storms, five hurricanes, and two major hurricanes. This lies at or slightly below climatological averages.

At face value, TSR’s projection might ease the concerns of (re)insurers fearing another active hurricane season similar to 2017 and 2018. However, this viewpoint would ignore the uncertainty ranges that TSR issues around their single-point activity forecasts.

Their ranges include the prospect that the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes could be above climatological averages; as TSR calls for between two to eight hurricanes and zero to four major hurricanes. And when you compare these ranges to all Atlantic hurricane seasons going back to 1900, around 84 percent of seasons fall within the TSR hurricane forecast range, and around 87 percent fall within their major hurricane forecast range. The figure below shows that these ranges encompass both 2018, a fairly damaging season, and 2013, a completely quiet season for (re)insurers. Only extremely active seasons (e.g. 2004, 2005 and 2017) are above TSR’s extended range forecast uncertainty.

Another metric used to assess overall activity is Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE), an index used to express the combined duration and strength of individual tropical cyclones and tropical seasons. TSR forecasts a 42 percent probability that the season will be below-average (ACE value <72), a 39 percent chance it will be near-normal (ACE value of 72-124), and a 19 percent probability that the season will be above-average (ACE value >124).

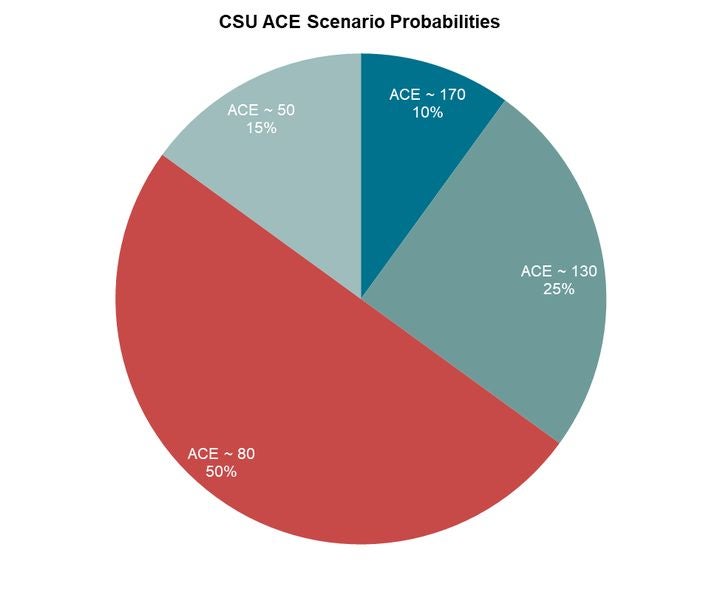

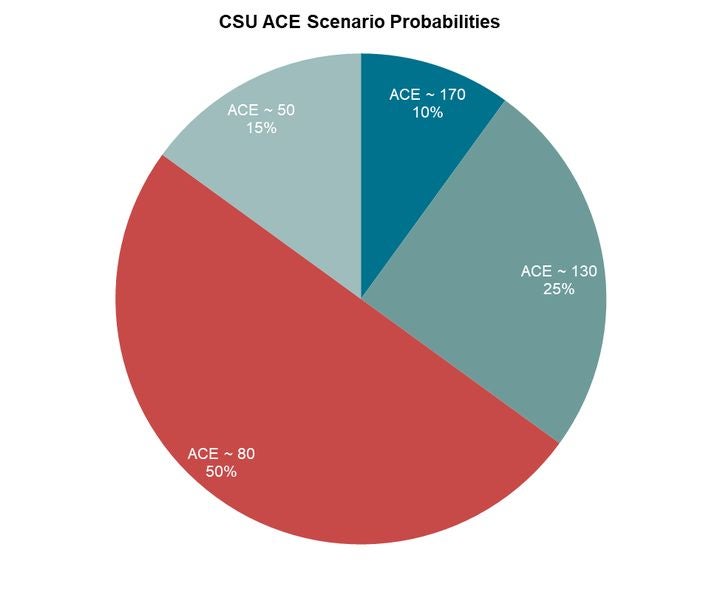

Acknowledging low forecast skill, Colorado State University (CSU) stopped providing quantitative extended range guidance in 2011 but continues to issue a qualitative discussion in December of features likely to impact future tropical activity. CSU assess five possible activity scenarios based on the strength of the Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation (AMO) and the phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

CSU anticipates a 50 percent probability that the ACE value will be around 80, which, based on climatology, would typically equate to eight to eleven tropical storms, three to five hurricanes, and one to two major hurricanes – and this is broadly in-line with the extended range forecast provided by TSR.

How Skillful are These Extended Range Forecasts?

The skillfulness of a seasonal activity forecast is generally determined by its statistical improvement over a climatological baseline period – or in other words, are these outlooks better than assuming average conditions?

Because seasonal activity forecasts are influenced by several interdependent and competing atmospheric and oceanic factors, the conditions that will emerge during the hurricane season are challenging to quantify and predict at extended time scales. Such factors include:

- The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

- Atlantic sea surface temperatures

- The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)

- Large-scale steering patterns

As a result, the forecast skill of seasonal activity outlooks at this lead time is generally very low. In its most recent report, TSR cites just a four percent forecast skill score for predicting the number of tropical storms at this lead time compared to the 1980-2018 period, with the forecast skill for major hurricanes at 14 percent.

As the year progresses, the uncertainty of the atmospheric and oceanic variables decreases, and the updated seasonal forecasts from April onwards can often be viewed with more confidence. Forecast skill generally peaks by early August, which coincides with the final activity forecasts from the main agencies, such as NOAA, TSR and CSU.

These varying estimates issued right up until the start of the season reflect the forecast changes to the complex interactions and interdependencies of the environmental and atmospheric factors.

We Can Still Learn Something from the Extended Range Forecasts

While extended range forecasts may not give full clarity on the upcoming season due to their low statistical skill, they do help identify which factors might be most important in determining the outcome of the season. For 2019, these factors appear to be ENSO, including its resultant implications on basin wind shear, and Atlantic sea surface temperatures.

In early February, NOAA announced that weak El Niño conditions had formed during January across much of the equatorial Pacific. These conditions are expected to continue through the Northern Hemisphere spring season and as things stand, there is a 50 percent probability that this phase will extend into the summer months. This will have implications for North Atlantic hurricane season activity as El Niño phases are typically associated with reduced activity.

TSR cites the expected continuation of the current weak El Niño conditions and the subsequent suppressing effect of the trade winds over the Caribbean Sea and tropical North Atlantic as the main factor behind its slightly below-average forecast. CSU also anticipates ENSO to be one of the key parameters crucial in determining Atlantic hurricane activity in 2019.

As always, RMS will continue to monitor these forecasts as they are released across the coming months and will publish a comprehensive summary of the seasonal forecasts and the oceanic and atmospheric conditions in June 2019. Regardless of the final number of named storms this year, it may only take one landfalling storm to cause significant loss and damage.