(Re)insurance companies are waking up to the reality that we are in a riskier world and the prospect of ‘constant catastrophes’ has arrived, with climate change a significant driver

In his hotly anticipated annual letter to shareholders in February 2019, Warren Buffett, the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway and acclaimed “Oracle of Omaha,” warned about the prospect of “The Big One” — a major hurricane, earthquake or cyberattack that he predicted would “dwarf Hurricanes Katrina and Michael.” He warned that “when such a mega-catastrophe strikes, we will get our share of the losses and they will be big — very big.”

The use of new technology, data and analytics will help us prepare for unpredicted ‘black swan’ events and minimize the catastrophic losses

Mohsen Rahnama

RMS

The question insurance and reinsurance companies need to ask themselves is whether they are prepared for the potential of an intense U.S. landfalling hurricane, a Tōhoku-size earthquake event and a major cyber incident if these types of combined losses hit their portfolio each and every year, says Mohsen Rahnama, chief risk modeling officer at RMS. “We are living in a world of constant catastrophes,” he says. “The risk is changing, and carriers need to make an educated decision about managing the risk.

“So how are (re)insurers going to respond to that? The broader perspective should be on managing and diversifying the risk in order to balance your portfolio and survive major claims each year,” he continues. “Technology, data and models can help balance a complex global portfolio across all perils while also finding the areas of opportunity.”

A Barrage of Weather Extremes

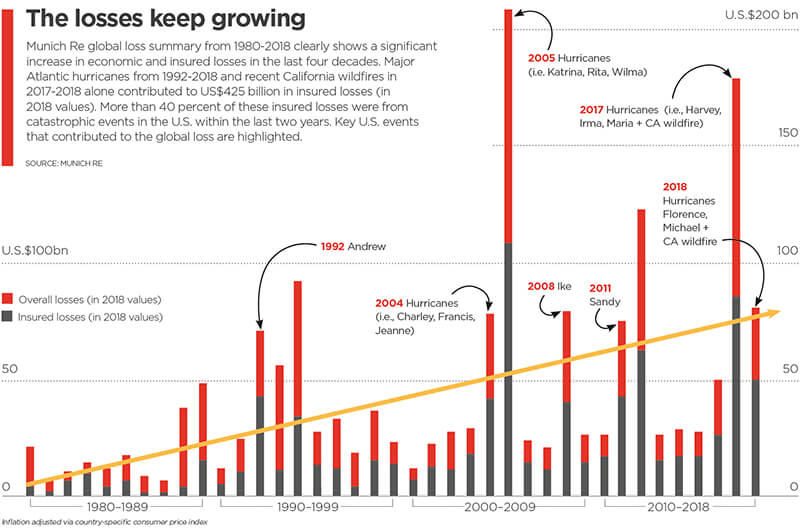

How often, for instance, should insurers and reinsurers expect an extreme weather loss year like 2017 or 2018? The combined insurance losses from natural disasters in 2017 and 2018 according to Swiss Re sigma were US$219 billion, which is the highest-ever total over a two-year period. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria delivered the costliest hurricane loss for one hurricane season in 2017.

Contributing to the total annual insurance loss in 2018 was a combination of natural hazard extremes, including Hurricanes Michael and Florence, Typhoons Jebi, Trami and Mangkhut, as well as heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, floods and convective storms.

While it is no surprise that weather extremes like hurricanes and floods occur every year, (re)insurers must remain diligent about how such risks are changing with respect to their unique portfolios.

Looking at the trend in U.S. insured losses from 1980–2018, the data clearly shows losses are increasing every year, with climate-related losses being the primary drivers of loss, especially in the last four decades (even allowing for the fact that the completeness of the loss data over the years has improved).

Measuring Climate Change

With many non-life insurers and reinsurers feeling bombarded by the aggregate losses hitting their portfolios each year, insurance and reinsurance companies have started looking more closely at the impact that climate change is having on their books of business, as the costs associated with weather-related disasters increase.

The ability to quantify the impact of climate change risk has improved considerably, both at a macro level and through attribution research, which considers the impact of climate change on the likelihood of individual events. The application of this research will help (re)insurers reserve appropriately and gain more insight as they build diversified books of business.

Take Hurricane Harvey as an example. Two independent attribution studies agree that the anthropogenic warming of Earth’s atmosphere made a substantial difference to the storm’s record-breaking rainfall, which inundated Houston, Texas, in August 2017, leading to unprecedented flooding. In a warmer climate, such storms may hold more water volume and move more slowly, both of which lead to heavier rainfall accumulations over land.

Attribution studies can also be used to predict the impact of climate change on the return-period of such an event, explains Pete Dailey, vice president of model development at RMS. “You can look at a catastrophic event, like Hurricane Harvey, and estimate its likelihood of recurring from either a hazard or loss point of view. For example, we might estimate that an event like Harvey would recur on average say once every 250 years, but in today’s climate, given the influence of climate change on tropical precipitation and slower moving storms, its likelihood has increased to say a 1-in-100-year event,” he explains.

We can observe an incremental rise in sea level annually — it’s something that is happening right in front of our eyes

Pete Dailey

RMS

“This would mean the annual probability of a storm like Harvey recurring has increased more than twofold from 0.4 percent to 1 percent, which to an insurer can have a dramatic effect on their risk management strategy.”

Climate change studies can help carriers understand its impact on the frequency and severity of various perils and throw light on correlations between perils and/or regions, explains Dailey. “For a global (re)insurance company with a book of business spanning diverse perils and regions, they want to get a handle on the overall effect of climate change, but they must also pay close attention to the potential impact on correlated events.

“For instance, consider the well-known correlation between the hurricane season in the North Atlantic and North Pacific,” he continues. “Active Atlantic seasons are associated with quieter Pacific seasons and vice versa. So, as climate change affects an individual peril, is it also having an impact on activity levels for another peril? Maybe in the same direction or in the opposite direction?”

Understanding these “teleconnections” is just as important to an insurer as the more direct relationship of climate to hurricane activity in general, thinks Dailey.

“Even though it’s hard to attribute the impact of climate change to a particular location, if we look at the impact on a large book of business, that’s actually easier to do in a scientifically credible way,” he adds. “We can quantify that and put uncertainty around that quantification, thus allowing our clients to develop a robust and objective view of those factors as a part of a holistic risk management approach.”

Of course, the influence of climate change is easier to understand and measure for some perils than others. “For example, we can observe an incremental rise in sea level annually — it’s something that is happening right in front of our eyes,” says Dailey. “So, sea-level rise is very tangible in that we can observe the change year over year. And we can also quantify how the rise of sea levels is accelerating over time and then combine that with our hurricane model, measuring the impact of sea-level rise on the risk of coastal storm surge, for instance.”

Each peril has a unique risk signature with respect to climate change, explains Dailey. “When it comes to a peril like severe convective storms — tornadoes and hail storms for instance — they are so localized that it’s difficult to attribute climate change to the future likelihood of such an event. But for wildfire risk, there’s high correlation with climate change because the fuel for wildfires is dry vegetation, which in turn is highly influenced by the precipitation cycle.” Satellite data from 1993 through to the present shows there is an upward trend in the rate of sea-level rise, for instance, with the current rate of change averaging about 3.2 millimeters per year. Sea-level rise, combined with increasing exposures at risk near the coastline, means that storm surge losses are likely to increase as sea levels rise more quickly.

“In 2010, we estimated the amount of exposure within 1 meter above the sea level, which was US$1 trillion, including power plants, ports, airports and so forth,” says Rahnama. “Ten years later, the exact same exposure was US$2 trillion. This dramatic exposure change reflects the fact that every centimeter of sea-level rise is subjected to a US$2 billion loss due to coastal flooding and storm surge as a result of even small hurricanes.

“And it’s not only the climate that is changing,” he adds. “It’s the fact that so much building is taking place along the high-risk coastline. As a result of that, we have created a built-up environment that is actually exposed to much of the risk.”

Rahnama highlighted that because of an increase in the frequency and severity of events, it is essential to implement prevention measures by promoting mitigation credits to minimize the risk. He says: “How can the market respond to the significant losses year after year. It is essential to think holistically to manage and transfer the risk to the insurance chain from primary to reinsurance, capital market, ILS, etc.,” he continues.

“The art of risk management, lessons learned from past events and use of new technology, data and analytics will help to prepare for responding to unpredicted ‘black swan’ type of events and being able to survive and minimize the catastrophic losses.”

Strategically, risk carriers need to understand the influence of climate change whether they are global reinsurers or local primary insurers, particularly as they seek to grow their business and plan for the future. Mergers and acquisitions and/or organic growth into new regions and perils will require an understanding of the risks they are taking on and how these perils might evolve in the future.

There is potential for catastrophe models to be used on both sides of the balance sheet as the influence of climate change grows. Dailey points out that many insurance and reinsurance companies invest heavily in real estate assets. “You still need to account for the risk of climate change on the portfolio, whether you’re insuring properties or whether you actually own them, there’s no real difference.” In fact, asset managers are more inclined to a longer-term view of risk when real estate is part of a long-term investment strategy. Here, climate change is becoming a critical part of that strategy.

“What we have found is that often the team that handles asset management within a (re)insurance company is an entirely different team to the one that handles catastrophe modeling,” he continues. “But the same modeling tools that we develop at RMS can be applied to both of these problems of managing risk at the enterprise level.

“In some cases, a primary insurer may have a one-to-three-year plan, while a major reinsurer may have a five-to-10-year view because they’re looking at a longer risk horizon,” he adds. “Every time I go to speak to a client — whether it be about our U.S. Inland Flood HD Model or our North America Hurricane Models — the question of climate change inevitably comes up. So, it’s become apparent this is no longer an academic question, it’s actually playing into critical business decisions on a daily basis.”

Preparing for a Low-carbon Economy

Regulation also has an important role in pushing both (re)insurers and large corporates to map and report on the likely impact of climate change on their business, as well as explain what steps they have taken to become more resilient. In the U.K., the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and Bank of England have set out their expectations regarding firms’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change.

Meanwhile, a survey carried out by the PRA found that 70 percent of U.K. banks recognize the risk climate change poses to their business. Among their concerns are the immediate physical risks to their business models — such as the exposure to mortgages on properties at risk of flood and exposure to countries likely to be impacted by increasing weather extremes. Many have also started to assess how the transition to a low-carbon economy will impact their business models and, in many cases, their investment and growth strategy.

“Financial policymakers will not drive the transition to a low-carbon economy, but we will expect our regulated firms to anticipate and manage the risks associated with that transition,” said Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, in a statement.

The transition to a low-carbon economy is a reality that (re)insurance industry players will need to prepare for, with the impact already being felt in some markets. In Australia, for instance, there is pressure on financial institutions to withdraw their support from major coal projects. In the aftermath of the Townsville floods in February 2019 and widespread drought across Queensland, there have been renewed calls to boycott plans for Australia’s largest thermal coal mine.

To date, 10 of the world’s largest (re)insurers have stated they will not provide property or construction cover for the US$15.5 billion Carmichael mine and rail project. And in its “Mining Risk Review 2018,” broker Willis Towers Watson warned that finding insurance for coal “is likely to become increasingly challenging — especially if North American insurers begin to follow the European lead.”