Over the past 15 years, we have witnessed some of the world’s largest possible recorded earthquakes that have had catastrophic impacts around the globe. But, looking back 30 years to 1989, we saw two smaller, but still significant earthquakes. The first was the M6.9 Loma Prieta event that hit the San Francisco Bay Area in October, an earthquake that is familiar to many due to its proximity to the city, and its level of destruction. However, less are aware of the other notable earthquake that year. December 28, 1989, is a memorable date for many Australians; as it marks the country’s most damaging earthquake in recorded history, and still remains one of Australia’s costliest natural catastrophes to date.

Despite its moderate magnitude, the M5.4 Newcastle earthquake caused widespread ground shaking, with insured losses of just under $1 billion AUD (US$690 million) at the time of the event (ICA, 2012), a loss which if the earthquake was repeated, RMS estimates would cost over $5 billion AUD.

Wide Area of Ground Shaking

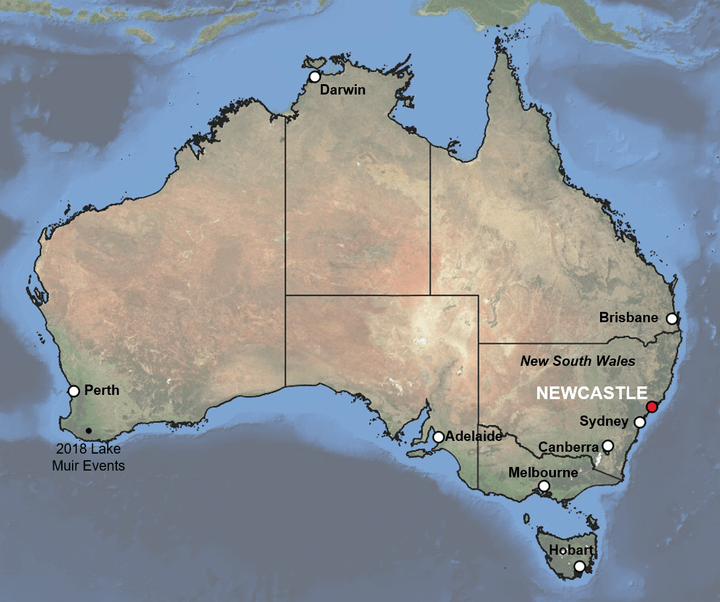

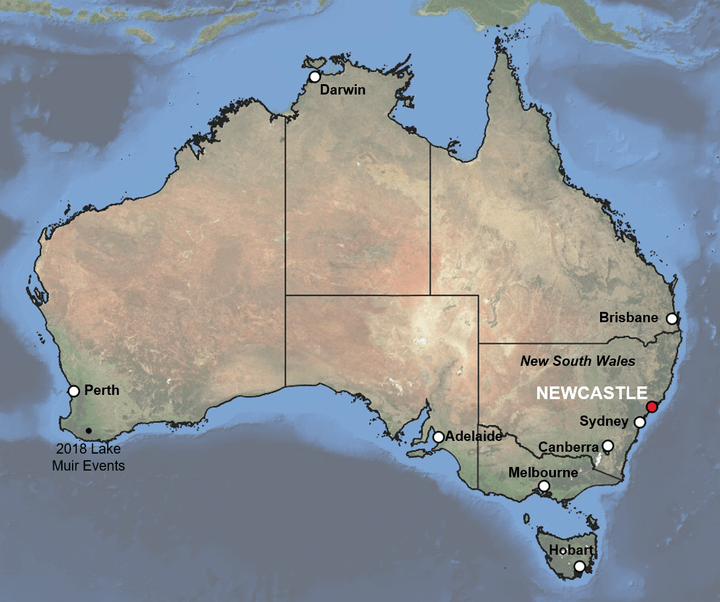

The shaking from the earthquake was felt over a large area, equivalent to a quarter of the 802,000 square kilometers (310,000 square miles) state of New South Wales. Given the wide area impacted by the Newcastle event, it was miraculous that the most significant damage was isolated to the east coast city of Newcastle (pop. ~322,000). In total, 50,000 buildings were damaged, and 300 were destroyed. The worst damage was to unreinforced masonry buildings, particularly older structures. However, newer buildings also experienced damage, including the Newcastle Workers Club, which collapsed and was responsible for nine out of thirteen deaths.

The relatively low seismicity in Australia is such that destructive earthquakes are rare. However, the Newcastle earthquake demonstrated the potential damage that could occur, even from a somewhat moderately sized event. The earthquake was located just over 100 kilometers (62 miles) from Sydney, which experienced shaking due to the event’s large footprint.

The sizable footprint was possible due to Australia’s stable continental tectonic setting, which implies that ground motion amplitudes decay more slowly. This results in larger event footprints compared to those in active crustal regions such as California. Thus, the potential for a wider exposure area to experience ground shaking is larger in Australia. But what if the event occurred closer to Sydney, or in fact, any state capital or large city in Australia?

In the past 30 years, Australia’s cities have seen steady population growth, and the national growth rate is high compared to other developed countries. Given that Australia’s state capitals are home to the majority of the population and are key drivers of national GDP, an event similar to 1989 in one of these key cities could have devastating consequences.

While recent urbanization in Australia follows the building code that was introduced after the Newcastle earthquake, a lot of older, more vulnerable buildings remain across Australia. If these buildings experience ground shaking comparable to 1989, there would be considerable levels of destruction. Analysis of an earthquake scenario similar to 1989, but for an event less than ten kilometers (6.2 miles) from Sydney’s central business district – close to the airport, results in almost six times the insured loss estimate for a repeat of the Newcastle earthquake.

Of course, there is a lot more exposure in Sydney compared to Newcastle, and widespread damage across the city and the significant loss, would make a Sydney earthquake challenging to recover from. On a nationwide basis, a loss of this magnitude would exceed the regulator’s (APRA) natural perils requirements for purchasing adequate reinsurance cover, and highlights the importance of considering the severity of low probability, but high consequence events.

Worryingly, it is possible that an even larger magnitude event could impact a key exposure area and would be even more devastating than both the Sydney scenario and the 1989 earthquake. To better capture the earthquake risk, since 1989 the Australia National Seismic Hazard map has been updated on several occasions to reflect the latest understanding of the earthquake risk. The most recent version was released in 2018.

This extensive update to the hazard map resulted in a significant reduction in the hazard across Australia. However, while this may lull society into thinking that the seismic risk is lower than previously thought, it does not mean that the risk has gone away. Rather, an event similar to 1989 will happen again in Australia and possibly even as a sequence of similar sized events, such as the 2018 Western Australia Lake Muir M5-type events, however, it is less likely to occur than we previously thought according to the latest assessment.

Thirty years on, and the Newcastle earthquake is still one of Australia’s costliest natural catastrophes. With the potential for a similar event to occur closer to key cities, and be potentially larger in magnitude, it is possible that there will be an even greater loss in the future. Despite the reduced frequency of events in the latest earthquake hazard map, the damage, disruption, and loss from a significant event would have considerable consequences for the economy, insurance industry, and wider society.